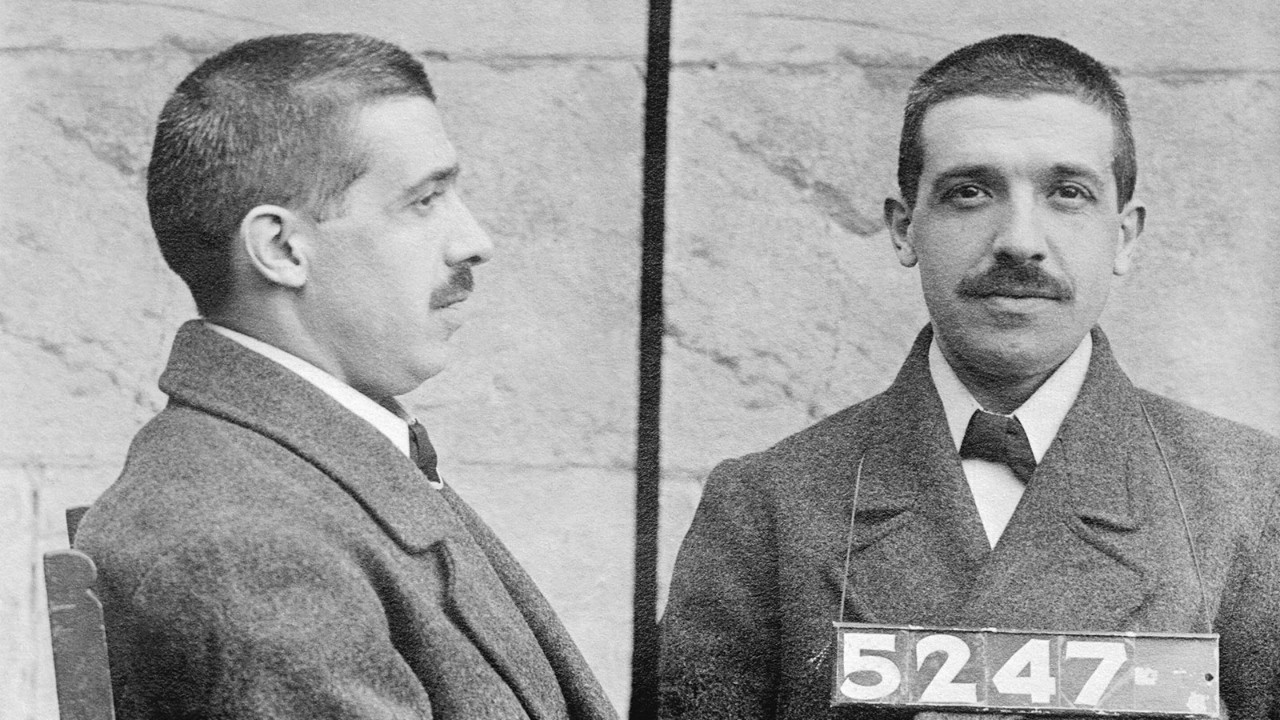

November 2020 was the 100-year anniversary of the imprisonment of Charles Ponzi – infamous creator of the fraudulent scheme to which he gave his name. Exactly a century later, Gutemberg Dos Santos, founder of AirBit Club, a cryptocurrency mining and trading company, was charged in the US with various offences relating to an alleged 'international investment scam', which, as described by the prosecutor, has all the hallmarks of a Ponzi scheme.

Ponzi’s notorious investment scheme remains popular with criminals today, and involves using the investments of subsequent investors to pay the earliest investors in an unsustainable scheme, typically promising huge returns.

‘People always seem to be taken in by the prospect of a quick return, so criminals just badge up the Ponzi in different ways’

Fraudsters like the Ponzi model because it’s simple, profitable and consistently works. ‘These schemes sell people a dream of making a lot of money quickly, and well above the market rate,’ explains Mark Button, director of the Centre for Counter Fraud Studies at the University of Portsmouth. ‘The bigger the return, the bigger the attraction.’

All Ponzi schemes follow the same principle: robbing Peter to pay Paul. The initial returns, generated by funds coming in from new investors, can be spectacular, drawing in more new investors, who believe they have found a winner. There is, though, no underlying business at all.

In Ponzi’s case, he claimed to have uncovered a fantastic investment opportunity, which involved buying discounted prepaid international reply coupons in Europe and redeeming them (for postage stamps, which could be sold on) at face value in the US – a perfectly legal form of arbitrage. People rushed to take up his phenomenal offer of a 100% return on the ‘investment’ in 90 days. However, the totally unsustainable investment model used funds from later investors to deliver returns for earlier investors, and collapsed within a year, leaving investors US$20m out of pocket.

Many incarnations

Ponzi schemes have taken many forms over time. ‘They will always be adapted,’ says Elisabeth Scott FCCA, head of forensic accounting at Bartfields Forensic Accounting. ‘People always seem to be taken in by the prospect of a quick return, so criminals just badge up the Ponzi in different ways.’

Even before Ponzi lent the fraud his name, scammers were operating similar rackets. They include Adele Spitzeder, a German woman who set up an investment bank in Munich in 1869, and at the height of her success was considered the wealthiest woman in Bavaria.

Then there was Sarah Howe, who opened a savings bank in 1879 in Boston, US, for unmarried women that promised extraordinary returns of 8% a month. The cynical Howe knew that women would be more likely to believe in her, although many men tried to invest too – some even dressed as women to try and gain access to her bank.

More recently, there was Bernie Madoff, ex-chairman of Nasdaq, who was jailed in 2009 for the world’s biggest Ponzi scheme, offering investments in stocks that ultimately led to investors losing US$18bn. And in 2010, Englishman Kevin Foster received a 10-year sentence for defrauding 8,500 victims of a total of £34m. Foster claimed he could take anyone’s £1 and turn it into £28 by using his ‘system’ to gamble on football matches and horse races, and made payouts to a few early investors to encourage them to get family and friends to sign up.

A cryptocurrency scam, if established, would just be a modern take on a very old theme. ‘In reality some people have legitimately made huge amounts of money from cryptocurrencies,’ Button says. ‘People hear of these returns and see it linked to an investment opportunity that fits the criteria.’ Indeed, ‘fear of missing out’ is a commonly used technique by Ponzi schemes.

Who’s to blame?

It seems easy to blame the victims for being dupes, but successful scammers are often charismatic individuals who provide reassurance to investors with the help of impressive-looking marketing. They also tend to let others do much of the promotion.

‘People see lavish websites, events and promotions and are told the initial investors have had high returns,’ says Scott. ‘They see someone before them who is believable. However, it is the recommendation of other investors that really benefits the criminal. He only has to sell himself once, then his victims will do the hard work for him.’

The frauds often have an element of exclusivity too. You had to be invited to join Madoff’s scheme. That can make it even more enticing.

‘It takes a special kind of person to run these schemes. They are ruthless, often charismatic, dominant people’

The criminals will often target groups they feel could be more vulnerable. Spitzdeler played on her supposed Christian piety. Madoff pursued Hollywood celebrities, synagogues and even charities. Foster concentrated his efforts on small low-income towns in South Wales.

‘It takes a special kind of person to run these schemes,’ says Button. ‘They are ruthless, often charismatic, dominant people. Anyone asking questions will need a strong character, as they find themselves threatened with legal action. It takes determined individuals to uncover these crimes.’

The reveal

Journalists and accountants have been behind some of the biggest arrests. Ponzi’s scam was revealed by The Boston Post, Spitzdeler’s by German paper Münchner Neueste Nachrichten, Howe’s by the Boston Daily Advertiser, and Madoff’s by financial analyst and forensic accountant Harry Markopolos.

The prospects for those trying to recover funds from an exposed scheme are not good. ‘If authorities can retrieve funds from the criminal, they will,’ says Scott, ‘but they don’t generally pursue investors. The lack of documentation means it’s hard to trace when money was received. None of the things you’d expect to find are there.’

The Ponzi remains well used by fraudsters. US authorities uncovered 60 such schemes in 2019, with US$3.5bn taken from victims, double the 2018 figure. But while Madoff, for example, is serving 150 years, the truly successful crook is the one nobody hears about. Taking the money and clearing out in time is the aim.

‘The Ponzi will always be around,’ says Button. ‘There will always be new, genuine, profitable businesses that can be replicated by Ponzi fraudsters.’ With a proven model that keeps delivering, the Ponzi scam remains only too capable of snaring the unwary investor.