It is almost 30 years since the Cadbury Committee’s influential report set out recommendations for a code of governance best practice for UK-listed companies.

Since then, the UK has experienced periodic waves of far-reaching reform triggered by concern at unexpected company failures, fraud scandals or poor corporate behaviour. Today, we are witnessing another significant shift, with numerous initiatives altering the corporate governance landscape.

The reforms focus on stakeholders and sustainability while bringing sharper accountability and tougher regulation

The government has two over-arching objectives: restoring public trust in business and reinforcing the attractiveness of UK capital markets. Although seemingly disparate, the governance initiatives are all interlinked. It is important to look at them together, identify the major themes and assess whether they are likely to achieve the government’s objectives.

Addressing failures

The current wave of reform began in 2016. Following public outcry over the collapse of BHS, the government’s green paper set out proposals for strengthening the UK’s corporate governance regime. Today, the wave resembles a tidal bore swelled by concerns over the liquidation of FTSE 250 Carillion and suspected fraud at AIM-listed Patisserie Valerie.

It encompasses new legislation, major restructuring of governance codes and ongoing consultation. The key components are:

- Legislation. Transparency and accountability are improved through significant new reporting requirements in the Companies (Miscellaneous Reporting) Regulations 2018 (the regulations). For example, all companies with more than 250 UK employees must include a statement of their engagement with employees in the directors’ report.

- Code changes. Major overhauls of both the UK Corporate Governance Code (the code) in 2018 and the UK Stewardship Code in 2020 reflect the changing economic and social climate. A new code (the Wates Principles) was published in 2018, providing a governance reporting framework for large private companies.

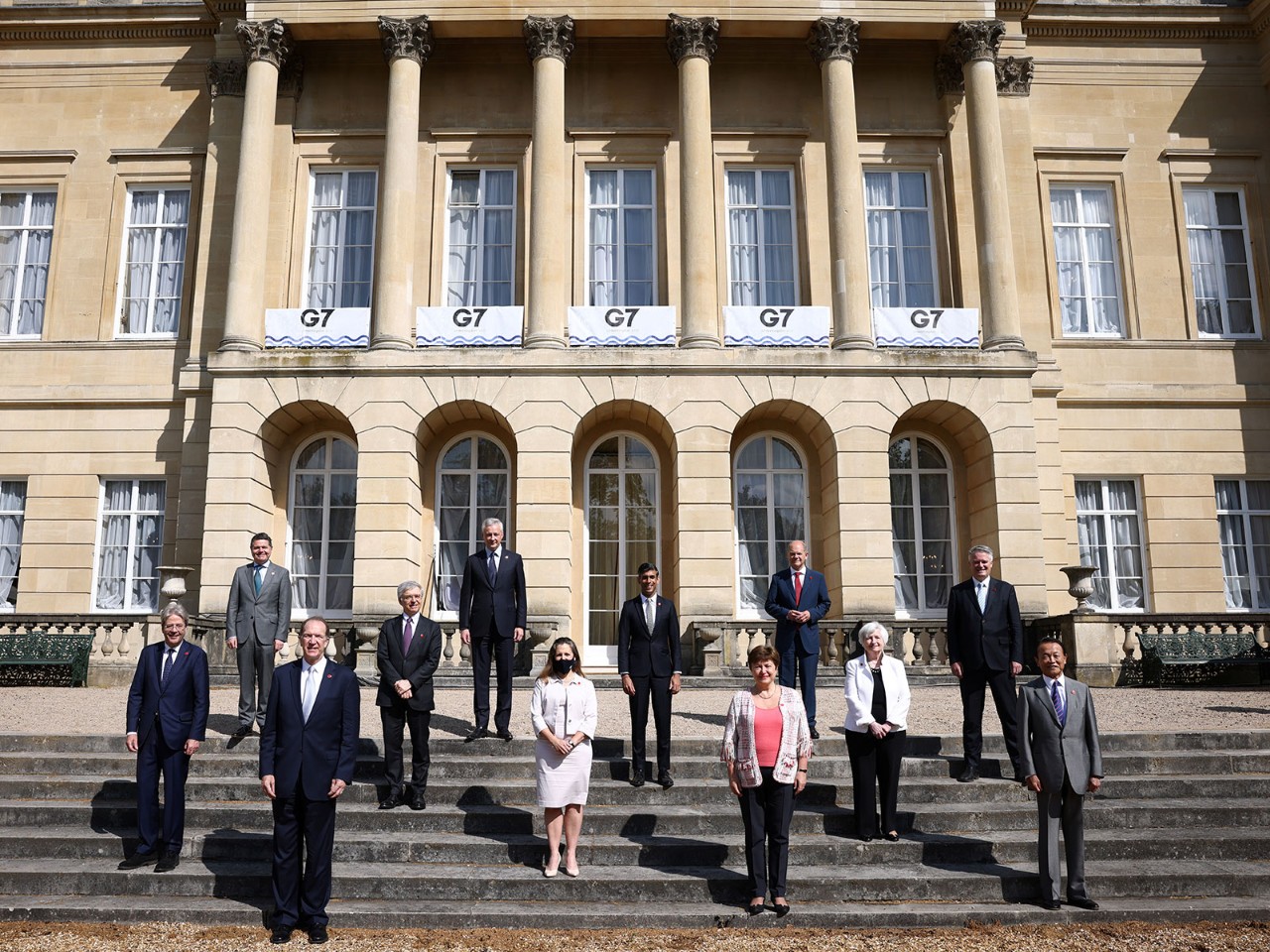

- Two significant ongoing consultations. Firstly, ‘Restoring trust in audit and corporate governance’ (the white paper) proposes wide-ranging regulatory measures to strengthen the governance framework of public interest entities (PIEs) and the way they are audited (see my recent article). Secondly, the UK Listings Review, chaired by Lord Hill, looks at options to strengthen the UK’s position as a global financial centre.

These activities are likely to transform the UK’s corporate governance framework, in three key ways.

Wider scope

Many more businesses are being brought under governance regulation and scrutiny.

The regulations and the Wates Principles open a new frontier because they draw attention, for the first time, to the quality of governance beyond listed companies. The regulations require large private companies to produce a ‘statement of corporate governance arrangements’ in their annual reports. The Wates Principles provide a framework against which they can report.

The white paper will extend the governance lens further. Proposals include expanding the definition of PIEs beyond publicly listed companies to include all large businesses of public importance – large private companies, certain LLPs and third-sector entities such as universities, charities and housing associations.

More stakeholder focus

The governance lens is being significantly recalibrated to reflect society’s changing concerns.

There is wider recognition today that good stakeholder engagement is crucial for business success. This is now embedded in the code.

Under principle A, the board’s role is to ‘promote the long-term sustainable success of the company, generating value for shareholders and contributing to wider society’. Sustainable success depends on aligning company purpose, strategy and values, while the code emphasises the importance of diversity, culture and succession-planning. Listed companies must have a specific mechanism for engaging with their workforce.

The climate emergency is also reflected. There is greater emphasis in company reports on non-financial metrics – including environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues – in the new Stewardship Code, too. The government is consulting on climate-related financial disclosures, with proposals to extend mandatory reporting using the framework of the global Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures to all publicly quoted companies, large private companies and LLPs.

Tougher regulation

Sharper accountability will become a feature of the UK’s governance regime.

The white paper contains wide-ranging proposals addressing public concern at perceived failures to hold directors and auditors sufficiently to account for corporate collapses. The centrepiece is a proposed new regulator, Arga, with enhanced investigation and enforcement powers.

Arga will provide more robust scrutiny of audit firms. The proposals include wide-ranging reforms: creating a new professional body for corporate auditors with a clear public-interest focus; a ‘managed shared audit’ regime for FTSE 350 companies (providing opportunities to challenger firms); and significant new obligations for detecting fraud.

Arga will have powers to investigate breaches by PIE directors (both executive and non-executive) of their reporting and audit duties and bring direct action. Directors will take greater responsibility for their company’s internal control systems under one of three options discussed.

The government is consulting on climate-related financial disclosures, with proposals to extend mandatory reporting

All the above reforms focus on stakeholders and sustainability while bringing sharper accountability and tougher regulation to the UK’s corporate governance framework. They may succeed in restoring public trust in business.

But will they reinforce the attractiveness of UK capital markets? Although investors will appreciate higher standards, there are concerns about increased audit costs and the risks of adding liability to directors through a US-style, ‘Sarbanes-Oxley-lite’ governance regime.

The Hill Review provides balance. It recommends wide-ranging changes to the UK’s listing and prospectus regime, with more flexibility to appeal to home-grown and international entrepreneurs, especially in fintech and life-sciences.

Offering easier listing rules combined with tougher regulation, this framework may succeed both in attracting business founders and in keeping international pools of capital in the UK.

Further information

Listen on demand to ACCA UK's webinar with CEO of the Financial Reporting Council Sir Jon Thompson, talking about the current consultation on proposals to strengthen the UK’s audit and corporate governance framework published by the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS).