Every now and then, people bring up this quote by legendary Liverpool Football Club manager Bill Shankly: ‘Some people believe football is a matter of life and death, I am very disappointed with that attitude. I can assure you it is much, much more important than that.’

This sentiment perhaps explains the furore that erupted, mainly in the UK, after it was announced that the six largest English Premier League (EPL) sides would be joining a breakaway European Super League.

Judging by how fiercely many players, coaches, officials, pundits, journalists, commentators and fans opposed the idea of the ‘big six’ (Arsenal, Chelsea, Liverpool, Manchester City, Manchester United and Tottenham Hotspur) joining a closed shop, it was not merely football that was at stake; it was what the game meant – and means – to these people and how much of it could have been destroyed if the Super League took off.

The owners and management of the clubs involved have been accused of turning their backs on the passion, culture, traditions, history and sense of community that underpin football in the UK.

Football today relies as much on business and investment acumen as it does on the abilities of players, managers and coaches, and fan loyalty

There had been talk of a new league of elite European clubs for years, but the April announcement was still a shock. It came at a time when Covid-19 prevents most fans from going to stadiums to watch their favourite teams play anyway. And there were no consultations with the key stakeholders – the clubs’ supporters or the sport’s governing bodies – before the 12 English, Spanish and Italian clubs agreed to form the Super League.

Love over revenue

A groundswell of public opinion has compelled the ‘big six’ to quickly withdraw from the project. And without their participation, the Super League cannot move forward. This has been hailed as a triumph of genuine football lovers over revenue-chasing businessmen.

Yes, the Super League announcement should have been handled with more sensitivity and less haste. And yes, the lack of engagement with stakeholders smacks of arrogance and tone-deafness. It will be a while before people forgive and forget these failures.

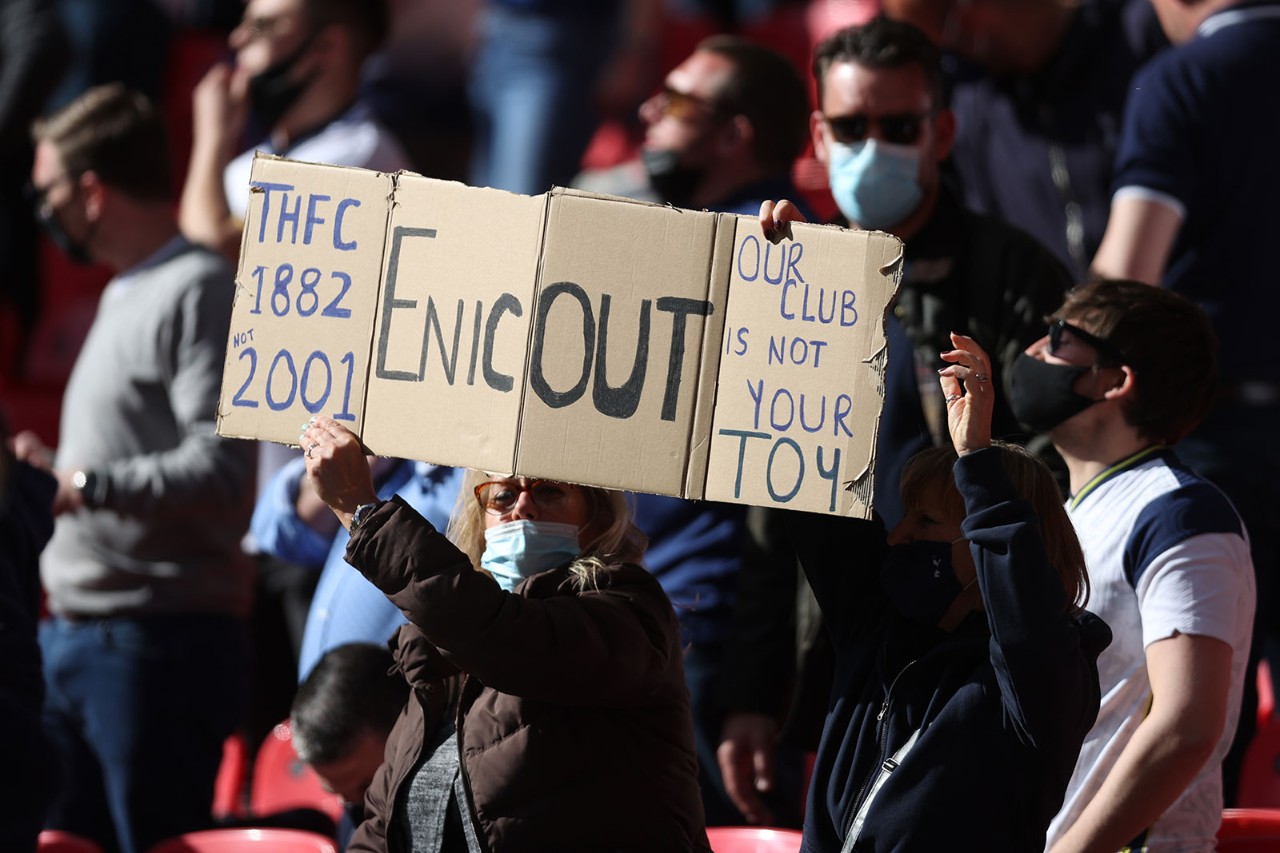

But it also has to be recognised that the reaction to the Super League news did spill over into unreasonableness, with potshots reserved for the owners and top executives of the clubs involved. They are often portrayed as outsiders who have no passion for football and fundamentally see the clubs as investment assets. Protests against the Super League saw people displaying messages such as: ‘Football belongs to us, not you’, ‘Football is for the fans’ and ‘Fans, football, owners. In that order’.

It was as if the critics were guided by another Shankly quote: ‘At a football club, there’s a holy trinity – the players, the manager and the supporters. Directors don’t come into it. They are only there to sign the cheques.’

Global enterprise

That attitude may have been valid in the 1960s and 1970s, but football today is a global multibillion-dollar enterprise that relies as much on business and investment acumen as it does on the abilities of players, managers and coaches, and fan loyalty.

Here is just one example of how much professional football in the UK has changed. In 1979, Trevor Francis became the country’s first £1m footballer when he signed for Nottingham Forest from Birmingham City. The transfer fees for several of the EPL’s best goal-scorers are currently £100m or more. In contrast, according to the inflation calculator on the Bank of England website, goods and services costing £1 in 1979 would cost £5.17 in 2020.

This massive growth of value in football is the result of teamwork on and off the field. Capitalism does not need to be defended, but solidarity within a club can be fragile. All the stakeholders want the club to win. But it gets harder when an us-against-them mentality sets in.

Why not turn to another piece of Shankly wisdom? A football team, he said, is like a piano because ‘you need eight men to carry it and three who can play the damn thing’. In other words, everybody has a role to play.