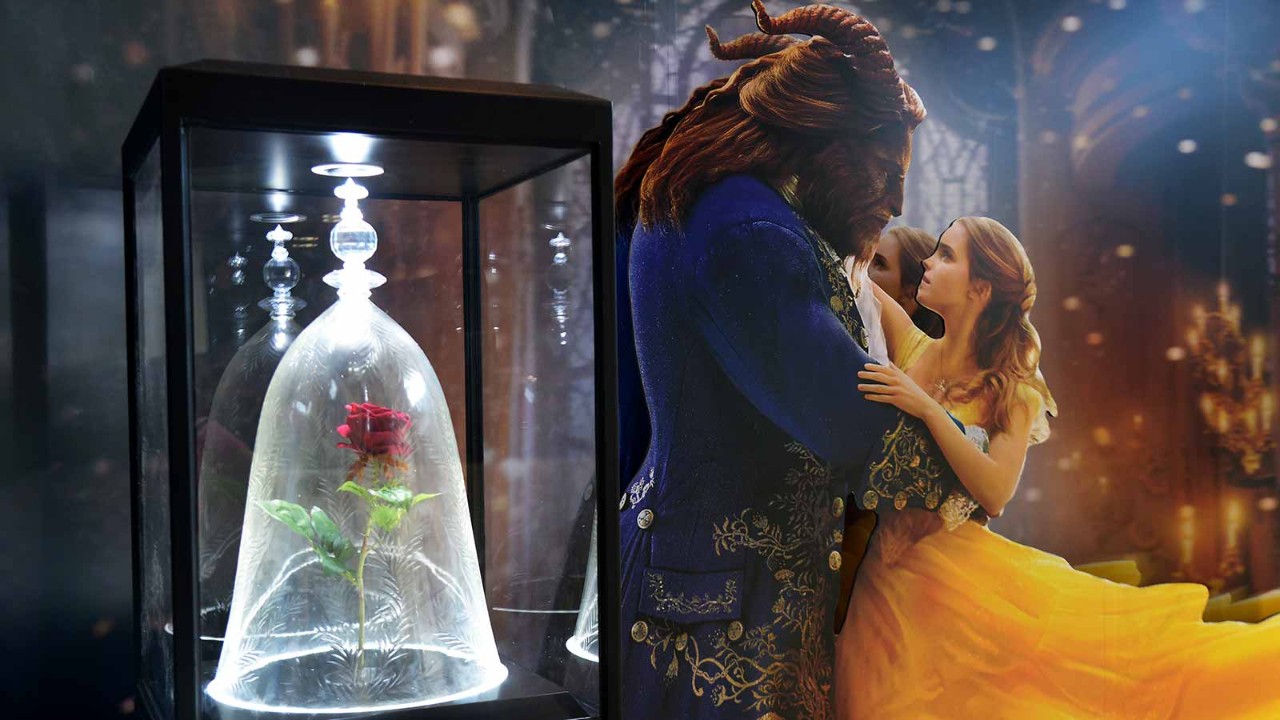

Some popular fairy tales have roots going back thousands of years. Beauty and the Beast is reckoned to be at least 4,000 years old, predating Homer’s Odyssey by more than a millennium. My non-scientific take on this is that humans are addicted to stories, and especially ones with a compelling narrative. One could also argue that this makes plagiarism one of the few skills whose utility transcends time.

I am not suggesting that annual reports should be treated as fairy tales, but I do think that companies should step back and think more about narrative and less about box-ticking. I would argue that behind every great company, there is a great story. Choose a company that you really admire and you will probably find yourself thinking about the things – the stories – that make it so compelling.

These stories or anecdotes may not necessarily be grounded in reality, and success may have been due to other, less interesting, factors, but that’s not the point. The point is that all humans everywhere love a story. This has huge implications for any company that wants to produce a compelling annual report.

Most companies in the northern hemisphere have a December year-end and start thinking about the next annual report after the summer break. This is therefore the perfect time to step away from the deepening swamp of compliance requirements and ask more interesting questions. What is our company for? What makes us different? What motivates us? How would we describe our business to a potential senior recruit?

Most of the blame can be laid at the feet of management for failing to articulate a narrative

Getting it wrong

Very few reports tell a good story, and I think the problem is getting worse, not better. Some of this is the fault of the standard-setters – for example, in their refusal to introduce useful cashflow statements. Some of the blame attaches to the advisers who think that the purpose of annual report is to win an award for producing the best annual report. But most of the blame can be laid at the feet of management for failing to articulate a narrative.

To be fair, I do accept that producing a compelling annual report is getting harder. The soup of acronyms gets thicker every year, particularly for disclosures about environmental, social and governance (ESG). TCFD, SASB, SBTi, UN SDG – the list keeps growing and it’s always tempting to just add a few pages for the latest burden. This, though, is a cop-out, not a solution.

Most companies are on a journey. They have a history, a recent past, a present and a future. The goal of an annual report should be to take readers on this journey, to put it in a sector or country context and help them understand how management sees the future. None of this conflicts with any statutory requirement and it can be woven into the compulsory content. Very few companies do it well.

Many companies use annual reports as, in effect, marketing tools. They are shown to suppliers, customers, politicians and journalists. Most of these readers will not understand the financial statements, and they will likely be unimpressed by moody photographs of the CEO looking statesmanlike. All of them, without exception, would be impressed by a good story well told. As it stands, most of them will be disappointed.

Two reports that have particularly impressed me are from UK manufacturer Spirax-Sarco Engineering and Swedish truck-maker Volvo. These are very different businesses, but both reports paint a picture that goes well beyond the numbers. Both integrate all the regulatory requirements without harming the flow of the report. Both have lots of illuminating case studies and graphics. And above all, both give readers a genuine feel for the business.