A confluence of forces is bending global supply chains out of shape. Take a pandemic, throw in a few long-term megatrends (deglobalisation, ESG, tech, e-commerce), pepper with inflation and high interest rates, sprinkle on some geopolitical tension, and you have a heady, disruptive brew.

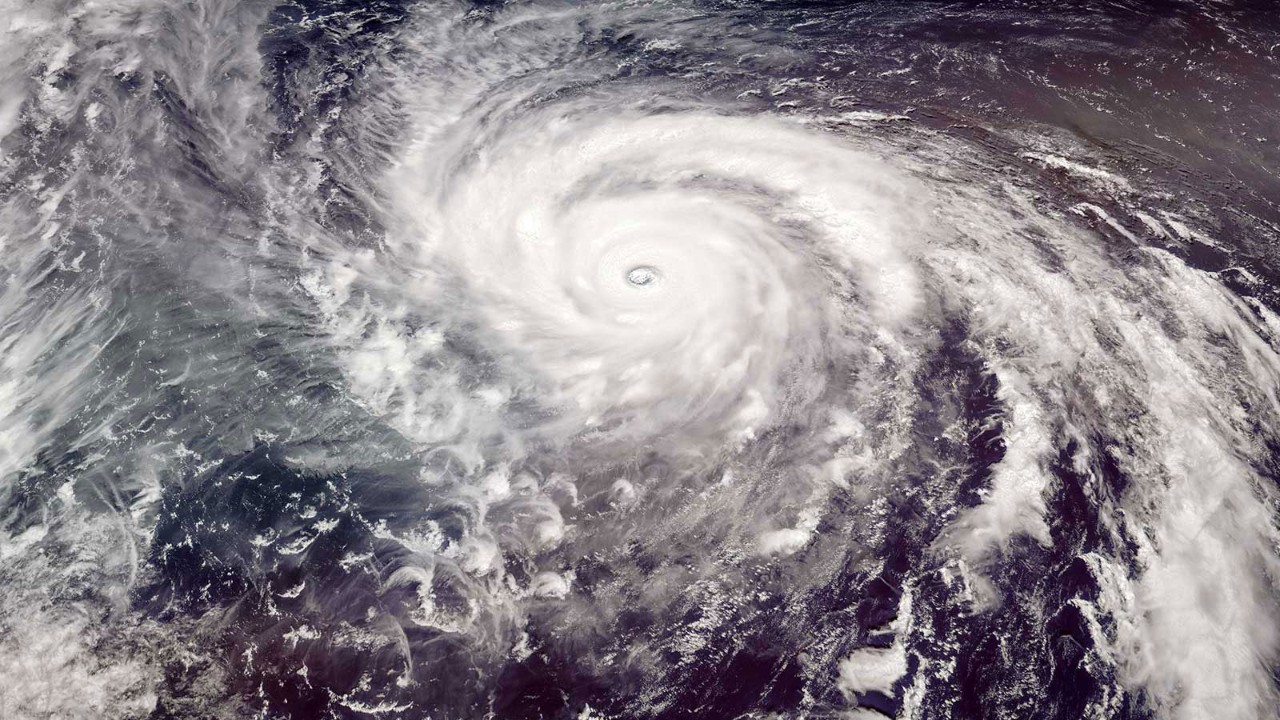

‘It’s a perfect storm,’ says John Cooper, a partner in the strategy and transaction team at EY-Parthenon. The pandemic exposed supply chains as being too linear: low cost but not very resilient nor agile, he says. ‘It used to be all about scale and cost, whereas now we’re moving from a supply chain to non-linear multiple chains and networks.’

‘Supply chain disruption is not going to get better any time soon’

Supply chain performance must now be viewed multidimensionally, Cooper says. ‘We still need cost efficiencies, but there needs to be a more nuanced and balanced view of performance and what drives value, taking in resilience, agility, sustainability and ESG, compliance and traceability. This is much more complicated to manage.’

Given high levels of uncertainty and volatility, it pays to think in terms of managing a series of transitions rather than temporary disruption, he adds. ‘If you think in terms of disruption, you might think the worst is over or you just need to manage through it. But it’s not going to get better any time soon, so you need to think to the future.’

Tech-enabled planning

Organisations need to assess their particular challenges and seek out efficiencies. According to Cooper, many are looking to reduce their product lines by 30%–40% to reduce complexity.

‘This will benefit everything from purchasing, sourcing and supplier management through to increased commercial focus and sales, completely transforming how a business is run,’ he says. ‘It will make it far more agile and responsive, and much easier to manage volatility.’

Most problems boil down to a couple of things, Cooper says. Those things are ‘a business’s capability, which can be improved through better technology and better people; but also how businesses are run, their ability to plan and replan, and therefore to respond in real time’.

He adds: ‘Previously, you could, for example, place orders for microchips 12 to 18 months in advance, but we don’t live in a world any more where we know what’s going to happen next year.’

AI and machine learning are having a major impact on logistics optimisation

We do, however, have data, and lots of it from all along supply chains, but how do you integrate, analyse and apply intelligence to it?

AI and machine learning are having a major impact on scheduling and planning, forecasting, risk reporting, measuring and mitigation, demand-sensing, spend analytics and logistics optimisation. They can automate decision-making, reduce operational redundancies and improve customer service.

According to McKinsey research, 61% of manufacturing executives have reported decreased costs and 63% increased revenues as a direct result of deploying AI in their supply chains.

CFO actions

Unwinding supply chains quickly is not easy, Cooper says. ‘It’s a strategic question, and this is where CFOs come in. There are going to be trade-offs, compromises, investment, decisions made that need to be right for the business. Management needs to understand protectionism and tariffs, and they need the visibility, tools and people who can manage that.’

Tejas Chaudhari, senior research analyst at Market Research Future, has quite a list of priorities for supply chain strategy re-evaluation. He suggests: ‘Reducing dependency on single sources; and prioritising resilience, cross-functional collaboration, technology adoption, risk assessment and scenario planning.

‘CFOs should conduct a thorough risk assessment, identify vulnerabilities and potential disruptions, including geopolitical, natural disasters and global health crises, and then prioritise mitigating these risks over cost-cutting in the short term.’

‘If suppliers are blaming inflation, CFOs shouldn’t take that as an answer’

Reducing costs in the supply chain is essential given high inflation, consumers feeling squeezed and the rising cost of borrowing. ‘But we are seeing a lot of cost-out programmes that are either not very ambitious or have stalled, or they’re not hitting the bottom line,’ Cooper says.

He adds: ‘CFOs have a duty to challenge the ambitions of supply chains. If the supply chain people are blaming inflation, saying that eventually it’ll come down and everything will be fine, I wouldn’t take that as an answer.

‘All actions require cross-functional arbitrated decision-making based on facts. CFOs need to act as arbitrators between the business and commercial functions that simply demand products and innovation without a thought to production cost and supply chain. Every new flavour, new colour, different pack size, etc, will have massive implications.

‘CFOs need to help the business understand the cost of changes to products; and the commercial side needs to understand and justify requests or remove a cost point if they want to add another.’

Regulatory impact

Also needed is a good understanding of trade – barriers, intellectual property, digital regulation, cross-border carbon tariffs to name a few. The EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), for example, comes into force in January, creating significant reporting requirements and increased costs on high carbon content bought in materials (more on this in AB in coming weeks).

‘There is a knowledge gap among businesses in understanding and interpreting the regulatory position and the need to lobby government,’ Cooper says. ‘CFOs can play a strategic role managing the changing face of regulation, tariffs and protectionism.’

Businesses need to think about the changing nature of tax structures and their supply chains. Many have been set up on the ‘principal’ model, with a legal entity established in a low-cost, low-tax jurisdiction to create and operate a supply chain there.

‘We’re starting to see the breaking up of tax hubs and the emergence of a multihub model’

‘This is evolving for multiple reasons, one of which is we have got global minimum tax rates now and proliferation of incentives and tariffs,’ Cooper says. ‘Lots of grants – for example, relating to energy transition – can be 50% of the cost of capital equipment. It’s resetting the role of tax and incentives, and it’s fundamental to the economics of, and the cost of reconfiguring, the supply chain.’

But how do you organise management hubs when the era of setting up an HQ hub overseas is now being challenged? ‘With the more complicated tax and tariff structures, the cost and scarcity of talent and needing to be nearer to your customers, we’re starting to see the breaking up of tax hubs and a need to put them in different places – a multihub model,’ says Cooper.

Any changes in supply chain management will require investment, but it doesn’t need to be done all at once – it’s a journey. ‘You need an evolutionary strategy, a roadmap,’ Cooper says. ‘It will take time, and the CFO needs to be at the centre of it.’

New-shoring

One measure to mitigate supply chain risk has been the move to ‘friendshoring’ – strengthening production networks with like-minded countries. It is a strategy favoured by the US government.

However, despite some global measures to ensure supply of critical materials – including recent legislation in the US and EU to ensure semiconductors are produced in the home countries – bilateral trade flows between the US and China reached a record high of US$691bn in 2022. The EU posted a widening negative trade balance in 2022 of nearly €400bn with China, its largest trading partner.

Nevertheless, supply chains do seem to be heading back home. EY’s 2022 report Why global industrial supply chains are decoupling found that 55% of companies based in Europe had nearshored or reshored in the previous 24 months, and 61% said they had made significant changes to their supplier bases.