The monkey mind is a Buddhist concept to describe feeling unsettled, restless or confused, or as executive coach and mindfulness trainer Karen Liebenguth describes it, our natural state of mind.

‘It means that our attention is always on something. Our evolutionary history has primed our minds in a certain way by default. When we humans lived out in the wild, we needed to be on the lookout for threats and dangers,’ she says.

'Monkey mind is not a sign of anything other than you are alive. However, it can be extremely annoying'

Psychologist and psychotherapist Dr Craig Kain also defines it as our natural state. ‘Our minds are designed to think, and they do so all the time. Most of the time we are not aware of our thoughts. We don't really notice the thoughts that cause us to tap our leg in time to the music going on in the background. It's only when we sit still that we can hear all the chatter in our brains. And for most of us it's a lot, which is why most people find it extremely difficult to sit still.

‘Monkey mind is not a sign of anything other than you are alive. However, it can be extremely annoying, can keep us up all night worrying, and can generally make life rather unpleasant.'

The monkey mind can be a vicious cycle of aggravation. Stress, anxiety, overthinking, lack of sleep, poor nutrition, caffeine and sugar, as well as environmental factors such as workplaces, social situations, busy commutes – all of these are capable, individually or together, of raising the volume of the chatter to an ear-splitting level.

The antidote

The antidote is usually some form of considered engagement, be it a mindfulness practice, acknowledging the chatter and its agitators, limiting what might be causing its peaks, and a healthier lifestyle involving better sleep, exercise and a balanced diet.

‘One way is to practice mindfulness meditation, which involves focusing on the present moment and observing one's thoughts without judgment. Another is to engage in physical activities, such as yoga or exercise, to help calm the mind and reduce stress,’ says health coach Yanira Puy.

‘Additionally, creating a daily routine and setting achievable goals can help provide structure and reduce feelings of being overwhelmed.’

'Free-association writing involves writing down all your thoughts. Don't judge yourself, simply put pen to paper'

Liebenguth’s four-step approach:

- Decide when the best time is for you to practice.

- Find a quiet space at home or at work. Take a moment to settle in and to settle down.

- Begin to direct your attention to your breath. Wherever you feel the breath most, keep your attention there.

- Occasionally ask yourself where your attention is now. The monkey mind does wander off. The training is to notice where your attention is and bring it back to your focus of attention (in this case the breath). It steadies the mind and strengthens your attention span.

‘Finally, it's important to take breaks and practice self-care regularly to avoid burnout and maintain mental and emotional wellbeing. In one’s professional life, one can practice prioritising tasks and creating a schedule, delegating responsibilities, and communicating effectively with co-workers to avoid unnecessary stress and anxiety.’

Another strategy is to engage in the practice of free-association writing, says mental health expert and career coach Dr Kyle Elliott. ‘This involves writing down all your thoughts for a set amount of time. Don't judge yourself or your thoughts, simply put pen to paper and write them down.’

Positive thoughts

Additionally, when you notice yourself engaging in negative self-talk, try reframing the statements in a positive, encouraging way, continues Elliott. ‘This may be challenging at first, but will get easier with practice.’

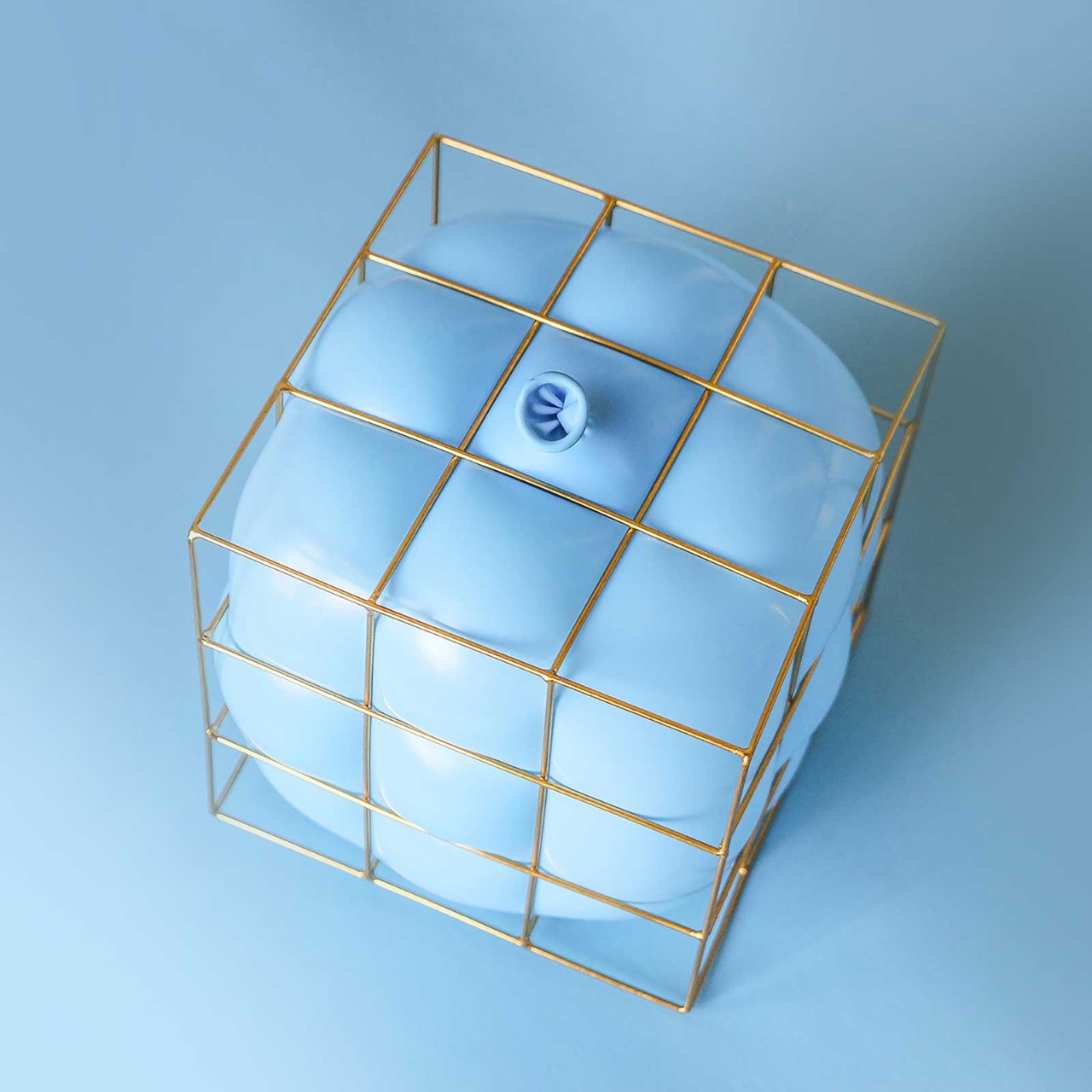

Kain advises clients to make friends with the monkey and treat it as you might an animal in a zoo – observe it in its habitat, not jump inside its enclosure to fight it. ‘We can simply observe the chatter, not engage with it, or yell at it to stop. We can simply take note of all the thoughts floating through our head and approach them with curiosity.’

Indeed, he goes on to say that naming our thoughts – angry, happy, anxious thought, etc – can be helpful. ‘It engages a different part of our brain than the one that typically experiences thoughts or feelings. But we need to exercise caution so as to not label our thoughts good or bad. The point is they are just thoughts and they will come and go.’

'Regular mindfulness practice for as little as 12 minutes per day does steady the monkey mind'

Mindfulness practice

A regular mindfulness practice can help tame and train our monkey mind, and one of the most common and effective involves being aware of our breathing. Kain suggests directing your attention to two points in the breathing cycle: where an inhalation becomes an exhalation and vice-versa. ‘Focusing on catching those two points can keep our minds occupied and cut down on the amount of inconsequential thinking we do.’

And don’t worry if you don’t do it perfectly, especially in the beginning. That’s not the goal. It’s more important to keep up a regular practice, and develop your ability to find calmness and notice an impact over time.

‘Training the mind is not an idea, but a practice,’ says Liebenguth. ‘The precise science of how much and what kind of mindfulness practice is most beneficial is a rapidly developing field.

‘However, we do know that regular mindfulness practice for as little as 12 minutes per day does steady the monkey mind. If you can do more than twelve minutes, great. The longer your daily practice, the more you will benefit, but it’s important to start small.’

More information

Organisational psychologist Dr Rob Yeung talks about how to manage worry in this video