Accounting for contingent liabilities can be used to ‘get around’ accounting rules and keep looming financial risks off a government’s balance sheet, according to one of the most eminent accountancy academics in the UK.

David Heald, emeritus professor at the University of Glasgow’s Adam Smith Business School, made the argument while speaking in March to the OECD working party on financial management and reporting.

‘There’s a temptation for the government to adopt policy forms that show them in a good light’

In a presentation entitled ‘Why the contingent liabilities of governments need to be better reported and monitored’, Heald outlined the inclination for some governments to move some obligations off balance sheet and into contingent liabilities.

‘There’s a temptation,’ said Heald, ‘for the government to adopt policy forms that show them in a good light when reflected in the accounting, whether they’re the government’s financial reporting rules, commercial accounting that the government now follows, or the national accounts prepared on statistical accounting principles.’

Under pressure

For Heald, scrutiny of the way contingent liabilities are used and reported is particularly important when government finances are strained and under close examination by opposition parties, the press, the public and financial markets.

Governments around the world are currently managing through a period of high inflation and have just emerged from the Covid-19 pandemic, which involved vast sums of additional spending. ‘We see increased fiscal pressure in many countries around the world at this point,’ says Alex Metcalfe, global head of public sector at ACCA.

‘With interest rates going up and many countries suffering debt distress as a result of the Covid period, they might feel driven to use these fiscal illusions.’

Contingent liabilities unpacked

Contingent liabilities – a term used for potential financial obligations that could arise in the future – are not actual liabilities, but could become costs a government has to meet depending on events. They might include future lawsuits from individuals or organisations, or the possibility of incidents such as environmental clean-ups or repayable taxes.

UK experience

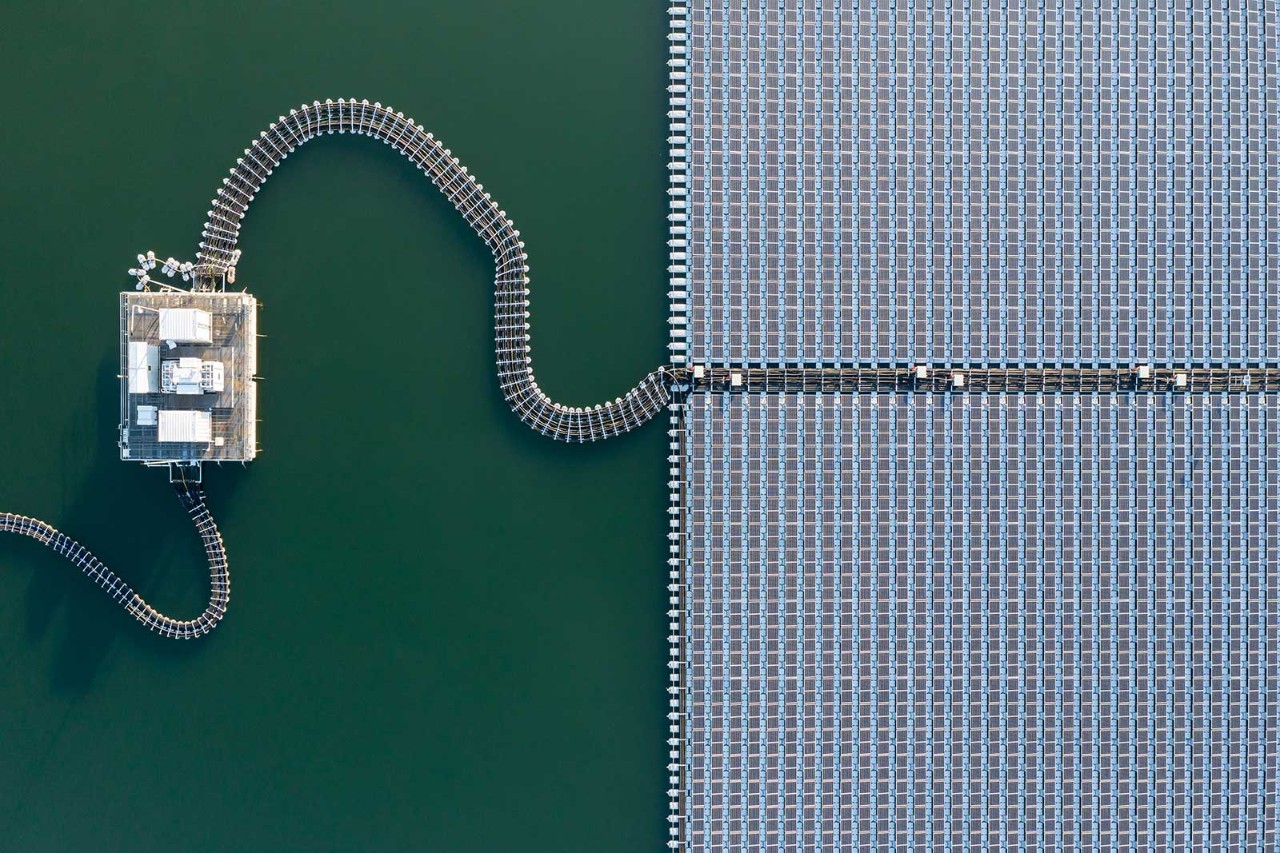

One of the most headline-grabbing categories for many governments are guarantees offered in relation to certain infrastructure projects, such as the UK’s Private Finance Initiative (PFI).

To give an example of how significant contingent liabilities can be, according to the UK’s last Whole of Government Accounts report, declared contingent liabilities stood at £464.1bn for 2019/20, an increase of £77.3bn on the previous year. Of that figure, £84.6bn is considered ‘non-remote’ and reportable under accounting standards. Remote liabilities in the UK are mostly made up of the Pension Protection Fund, which, at the time of reporting, stood at £250bn.

Heald’s unease is not the first time concern has been raised about the option of shifting costs off balance sheet through contingent liability categorisation. Its use in PFI became a long-running sore in British public policy discourse. The initiative covered infrastructure building projects paid for by the private sector while the contractual terms meant the government was ultimately responsible for the costs through unitary charges and guarantees.

In 2018, UK PFI projects were discontinued largely because of the potential liabilities it generated for government finances. But that doesn’t mean contingent liabilities are not a concern now. According to many observers, they re-emerged following Brexit and then, more recently, as a result of the pandemic, which saw the government offer vast sums in loan guarantees.

The use of guarantees could be the most efficient means of handling project costs, but only up to a point

Accrual factor

There is also a structural driver of temptation. Many more countries are switching from cash to accruals accounting. Currently only around 25% of countries use accruals, including the UK, but ACCA expects that number to rise to around 75% by 2030.

‘The reason that’s important,’ says Metcalfe, ‘is because in a “cash” environment, you’re not thinking about contingent liabilities, or more detailed disclosures, and you don’t have a balance sheet.’

Accruals accounting does use balance sheets and allows for reporting of contingent liabilities. Used correctly, the process can provide a form of clarity, as Metcalfe points out, but it can also be used to game the near-term potential liabilities faced by a government.

Motivations

That means government should be taking greater care when classifying fiscal risks. Heald’s argument is that use of guarantees, whether for PFI or other issues, could be the most efficient means of handling project costs, especially large ones. But only up to a point. His warning is made more poignant given that PFI structures continue to be widely used in jurisdictions around the world.

When governments become obsessed with how they score against accounting rules, that’s when you head into trouble

‘Using things like PFI for reasons of efficiency is potentially a useful instrument,’ Heald said. ‘When PFI is used simply to get around the [accounting] rules, it leads to problems. It leads to distortions about the kind of projects one adopts, and it also leads to disbelief in the policy instruments.

‘The point is governments have a range of different ways they can do things. When they become obsessed with how they will score against the accounting rules, or the statistical rules, that’s when you head into trouble.’

Heald emphasised the responsibility of government to review its policies. ‘Governments need to recognise that they should evaluate PFI and guarantees as instruments and test them against conventional procurement,’ he said.

That process offers a role for the professional accountant in government decision making, according to Metcalfe. ‘When you have a policy decision,’ he says, ‘is there a professional accountant in the room who is going to talk about not just the implications for financial reporting, but what it means for the financial health of the public sector? That’s an expertise of which we don’t see enough.’