For a brief period in the early 1990s, Indonesia was the darling of foreign investors. Capital poured into its then burgeoning manufacturing, tourism and finance sectors, and funds flowed into its booming stock market.

Then came the shocking economic and political collapse of 1997-98 during the Asian financial crisis. A long period of underperformance followed, during which Indonesia was largely ignored by global investors.

But now things are changing. In the past decade, Indonesia’s government has worked hard to improve the country’s fundamentals. If it keeps up the pace of reforms, Indonesia can build on this and enjoy a surge in economic growth from the not-so-bad 5% average of recent years to a more exciting 7%.

Could do better

Indonesia’s performance has been respectable but not exciting, certainly not in comparison with some of its Asian neighbours. The comparison with China is the starkest. While the average Indonesian was once three times richer than the average Chinese, China has not just caught up but is now well ahead – its living standards reached parity with Indonesia by 2009, and the gap has widened since then.

Indonesia has much going for it. Its demographics are excellent and it has substantial reserves

But Indonesia has much going for it. Its demographics are excellent, relative to China and Vietnam, providing it with deep pools of labour and an expanding middle-class consumer market. It can also benefit from further urbanisation. It has substantial reserves of oil, gas, coal, nickel, copper and bauxite, plus a dominant position as a producer of palm oil, the edible oil of choice for much of the world.

There are globally competitive clusters of manufacturing around Jakarta and elsewhere that produce goods such as motorcycles and labour-intensive goods such as garments and shoes. This means it could benefit from the reconfiguration of supply chains, and attract some of the production that is leaving China.

Its tourism sector alone could drive its economy forward. Indonesia has yet to fully exploit its 17,000 islands offering pristine beaches and some of the best diving spots in the world, not to mention its extraordinary historic sites such as Borobudur.

Missing ingredients

What Indonesia has not quite succeeded in doing is moving up global value chains in the way that China and South Korea have. Indonesia’s performance in global rankings of ‘economic complexity’, a measure of a country’s true development, has been mediocre, even as its neighbours have made substantial progress in exporting knowledge and technology-intensive products that enabled beneficial diffusion effects to the rest of the economy. Also, the proportion of mid-to-high tech manufacturing exports has stagnated at a low level, in contrast with its peers.

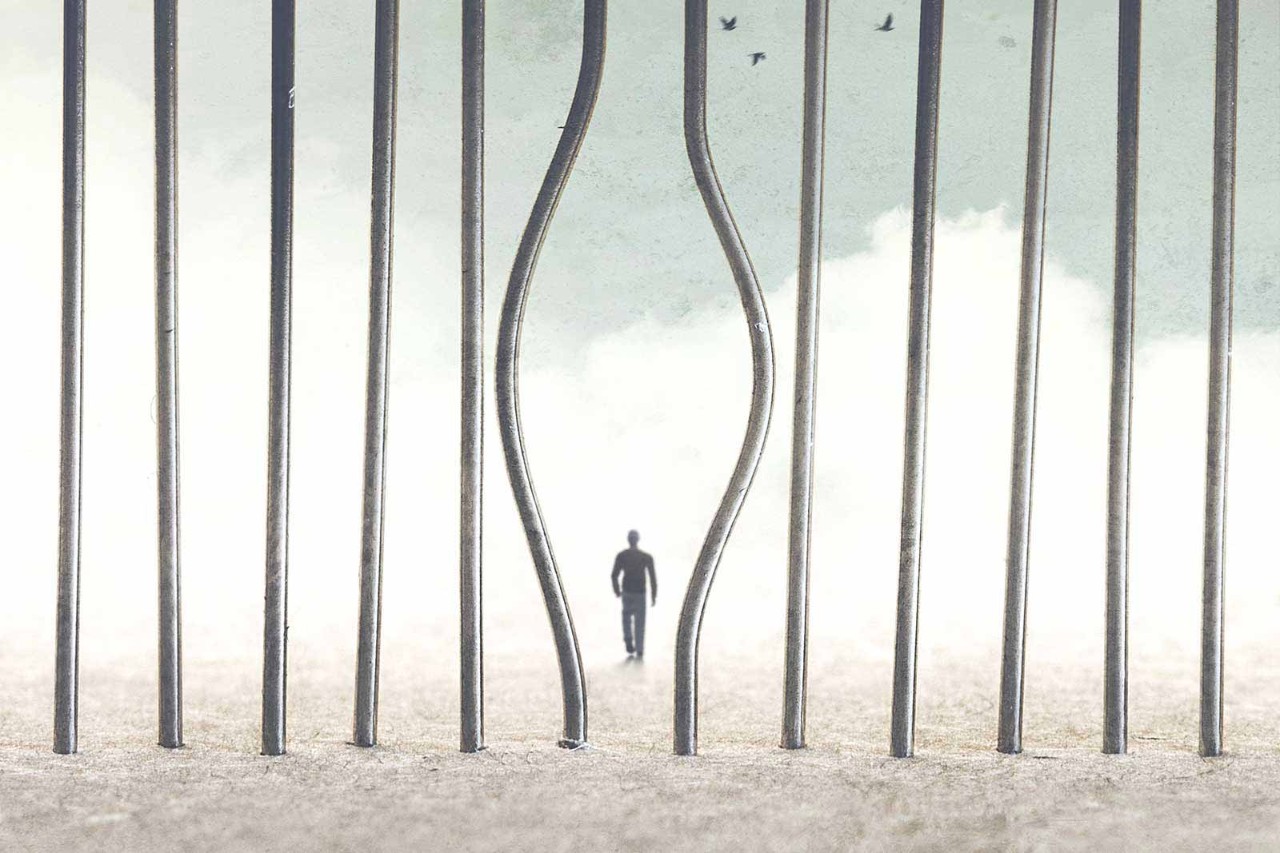

The underlying reason for this has been some reticence on the part of policymakers to open its economy more fully to global competition. Protectionist policies allow domestic firms to maintain their hold on the home market – but the lack of competition inhibits efficiency and inflates domestic costs. Industrial policies, such as the push for ‘downstreaming’ have had some success in the nickel sector, but have raised concerns among foreign investors about future policies.

The increasing pace of digital transformation should allow for a greater ease of doing business

Another reason is Indonesia’s slow progress in human capital development. This can be remedied by better policies. The political will is there, as can be seen in the constitutional commitment to spend 20% of the national budget on education.

However, for this budgetary spending to deliver the desired results in terms of better scholastic achievements in comparison to competitor economies, it will need further reforms in the education system.

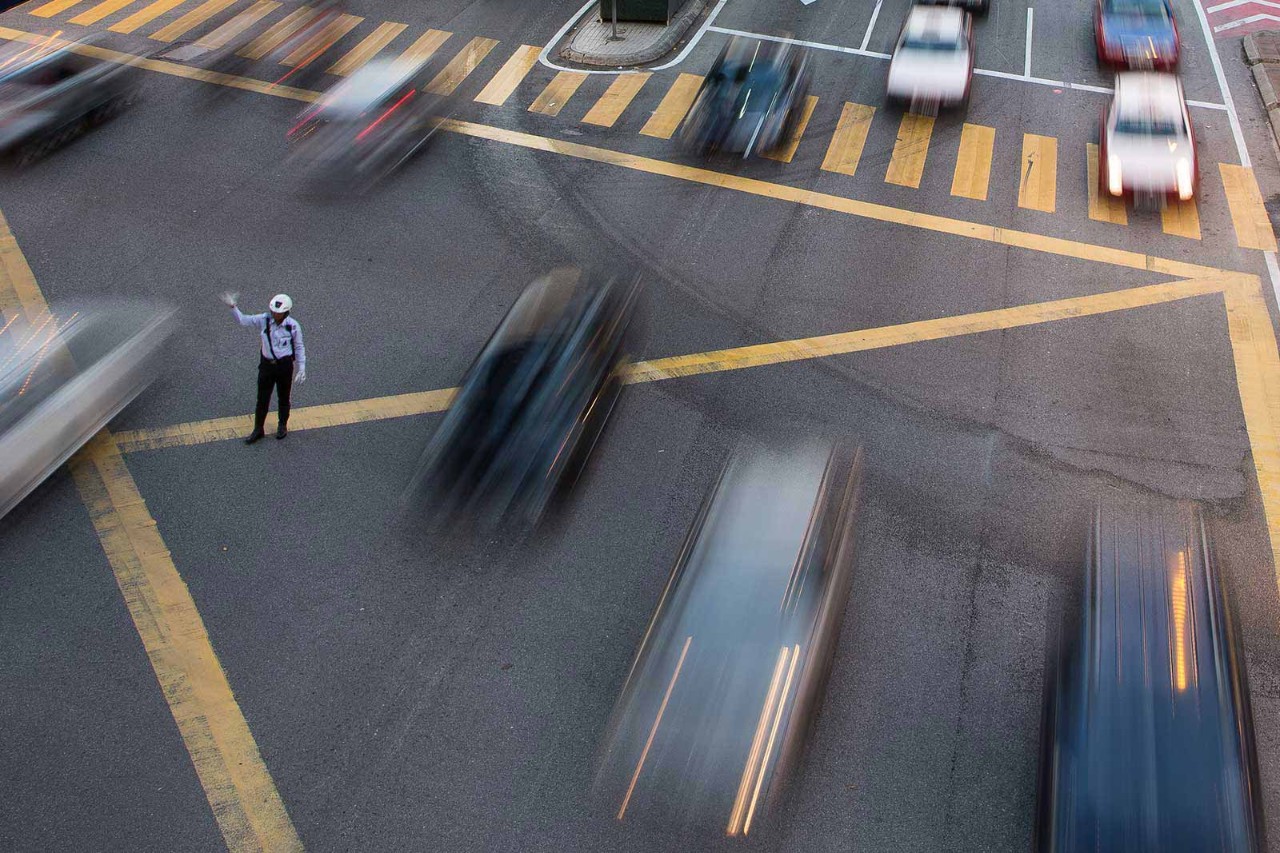

Other constraints are also amenable to reforms and this is where the government continues to make progress. Logistical difficulties which have led to high monetary and time costs of transporting goods are gradually easing as progress is made on infrastructure. The increasing pace of digital transformation in Indonesia should also aid in enhancing the efficiency of government, allowing for a greater ease of doing business.

Reasons for optimism

Indonesia has slowly improved its economic fundamentals through several political administrations, reflecting a broad consensus in the country in favour of pragmatic measures to enhance its competitiveness and attractiveness to foreign investors.

The bold liberalisation of its labour market and the rationalisation of fuel subsidies were politically unpopular, but were still carried out. The longstanding commitment to fiscal prudence and rigorous monetary policy has also boosted policy credibility.

All this gives confidence in Indonesia achieving a surge in economic growth.