Ireland’s place in a turbulent, uncertain Europe may be a debate for our times, but it is also one where the pages of history have lessons for us, as a new exhibition at the National Museum of Ireland (NMI) demonstrates. Words on the Wave explores the inordinate influence of Irish missionaries on early medieval Europe through a rich array of artefacts – the centrepiece being 17 manuscripts, loaned from the abbey of St Gallen, Switzerland, written by Irish scribes and returning home for the first time in 1,000 years.

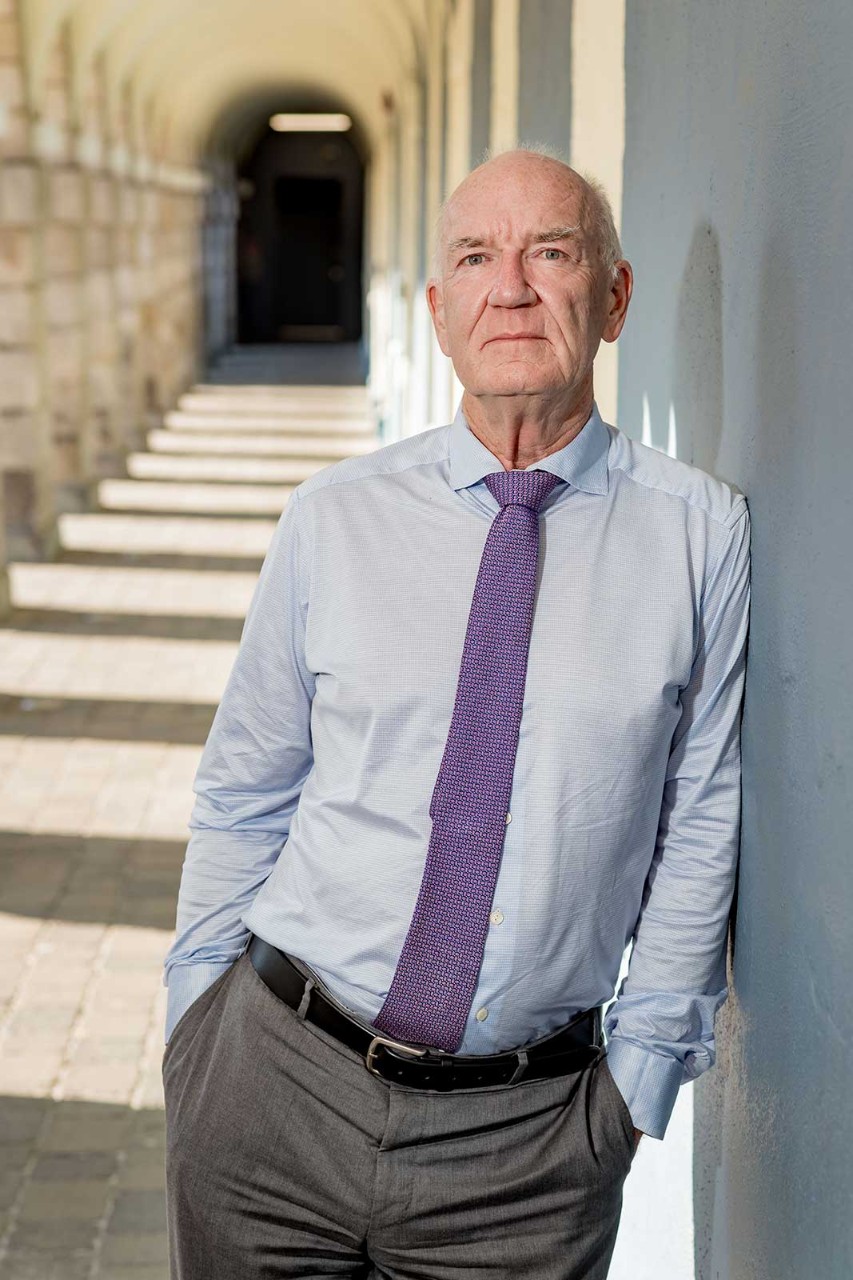

Joining the NMI in 2019 as head of finance and procurement services, Mark Sherry FCCA has no doubt the exhibition will be a hit with the public – and a good feeling for why. ‘What I learned very quickly coming into this role is that everybody cares about our history,' he says. 'There’s a huge level of knowledge out there among individuals and organisations around particular objects. People are looking to know more about where we have come from and to have the fine details filled in.’

‘We don’t acquire something simply because people believe we should’

Acquisition questions

Evolving from the work of the Royal Dublin Society in the 18th century, the NMI today extends across four public sites (see box). Most intriguing, at least for those raised on Raiders of the Lost Ark, may be its fifth site, the Collections Resource Centre in Swords, the main storage depot.

‘Around 95% of the national collection is held in storage at any one time,’ Sherry says, adding that those contents could easily fill multiple new museums if resources allowed.

The NMI has in excess of four million artefacts in its possession, of which almost 450,000 have been digitally catalogued to date. Work is ongoing through a number of projects to improve both digital and physical access. Adding to the collection is a live, ongoing process, and there will always be strong views and debate about what should be included.

‘When there are major auctions or an important private collection is being distributed, agreement is reached on whether particular items should be acquired,’ Sherry reflects. ‘It’s important, however, we don't have a hundred of the same kind of item, or that we don’t acquire something simply because people believe we should.’

‘We had to identify experts who could help us remove a whale’

National Museum of Ireland branches

1792

The Royal Dublin Society acquires its first ‘museum’ collection, the Leskean Cabinet

1855

Natural History Museum, affectionately known as ‘the Dead Zoo’, opens

1890

Kildare Street Museum opens, renamed National Museum of Ireland in 1921

1997

National Museum of Ireland – Collins Barracks opens, specialising in decorative arts, design and military history

2001

National Museum of Ireland – Country Life opens in Co. Mayo

One recent addition shows it’s not just a question for the antiquarians or even the public purse. Irish musician Rory Gallagher’s 1961 Fender Stratocaster guitar ‘was a significant acquisition for us, done in collaboration with Live Nation. They bought the guitar and donated it to us, through the Section 1003 tax relief. A lot of finance and compliance work was needed, but the end result is a really cool piece of history we now hold on behalf of the nation.’

Specific skills

Running on an annual budget of around €25m, the majority supplied by the Exchequer, Sherry says that while it ‘is hard to measure the productivity of a museum in financial terms’ he has no doubt ‘the taxpayer gets great value for money. Ultimately, you have to look at other metrics, such as the value of having items available and the response of the public to them.’

The prominence of procurement in Sherry’s job title testifies to expectations around transparency across the public sector but also reflects a role where highly specific skills and services are called for. When the Natural History Museum was emptied of its contents a few years ago (the technical term is ‘decanted’) to prepare for refurbishment ‘we had to run a procurement competition to identify experts who could help us remove a whale,’ Sherry recalls. ‘Ultimately, we found a group in the Netherlands who had the necessary expertise’. The exacting removal process is entertainingly documented in a YouTube video.

Passion and experience

Prior to the NMI, the Irish Equine Centre was the mainstay of Sherry’s career, reflecting a personal passion that has driven him throughout his life. ‘After school, I hadn't a clue what I wanted to do so the first job I took was at a local stable, because I loved horses.’

A flair for administration would see him take on roles in a number of member organisations in his early 20s, while also pursuing the ACCA qualification. He completed his exams soon after joining the Irish Equine Centre, where a 30-year career would culminate in the role of head of finance and administration.

'There's is a growing community of Mongolians in Ireland'

CV

2019

Head of finance and procurement services, National Museum of Ireland

2017

Head of finance and administration, Clondalkin Addiction Support Programme

1987

Joins Irish Equine Centre, rising to head of finance and administration and becoming honorary consul for Mongolia in Ireland

This was not, however, the most eye-catching title he enjoyed there. ‘In partnership with the EU and the Department of Agriculture, the Irish Equine Centre administers a number of international development projects,’ he explains. Administration of scientific research projects, technological skills transfer programmes and the development of research partnerships across the EU were all part of Sherry's remit in his time there.

Among the countries linked to the development projects was the East Asian nation of Mongolia, and Sherry would forge close relationships with the equine community there, ultimately leading to his appointment as honorary consul to Mongolia.

As diplomatic posts go, he says dryly, ‘it was not the Ferrero Rocher kind. There's is a growing community of Mongolians in Ireland, with people in need of consular assistance and support from time to time. I was delighted to be able to help in any way I could.’

New direction

Taking early retirement from the Irish Equine Centre in 2017, Sherry admits that while he relished the chance for down time, he quickly found himself drawn to new opportunities. The chance to work with Clondalkin Addiction Support Programme brought a renewed sense of purpose and allowed him use his core finance and administration skills in a fresh way.

‘It was an extraordinary experience – very different from any world I had been exposed to previously,' he says. 'Before it, I had no real understanding of what the life of a person in the addiction space was.’

Freshly energised from the experience, Sherry has continued to put retirement plans on pause. Now in his sixth year with the NMI, Sherry won’t be the first to observe that the rewards of working in the public sector can be tempered by the reality of ‘a level of scrutiny around finance that doesn't exist in other organisations.

'While the core objectives of financial recording remains unchanged, public sector accounting also has an additional layer of scrutiny attaching to governance processes and capital project management, all of which fall within the finance role at the NMI.'

Sherry is currently overseeing the NMI's migration into the new public sector financial services network. 'This is a complex and challenging project for the public sector but one which offers many benefits for public sector accounting,' he says.

He praises the ACCA public sector panel for being a forum for constructive debate and discussion on topical matters. ‘I'm very proud of being a member of the ACCA. In the era of AI and Big Data, its focus on accuracy, on information that is timely and fit for purpose, is really important to me,' he says. 'I feel very lucky to be able to apply those skills in an area that I have a deep interest in and in a role in which I can have some impact.’