Barely a week goes by without some leader – either in business or politics – being exposed for having behaved in a way that is dishonest, manipulative, corrupt or otherwise underhand. Such reports can sometimes make it appear as if leadership and bad behaviour are inextricably linked.

Business leaders who do the right thing command far less attention in the media, perhaps because wrongdoing typically makes for better headlines. However, most large-scale studies of leaders suggest that it is ethical rather than unethical behaviour that gets the best results.

Private sector employees led by ethical leaders felt more engaged and experienced greater mental wellbeing

More innovative

For instance, in a study of 80,316 public sector workers, researchers Zeger Van der Wal and Mehmet Akif Demircioglu at the National University of Singapore found that employees led by ethical leaders tended to be more innovative.

Another investigation led by Huma Sarwar at the University of Brescia in Italy found that private sector employees led by ethical leaders felt more engaged in their work and experienced greater mental wellbeing. This was true of employees in both Italy and Pakistan, suggesting that the benefits of ethical leadership are not limited only to developed countries.

More than 114 studies have examined the links between ethical leadership and firms’ financial performance. Analysing all of these prior studies, a team led by Raiswa Saha at India’s SRM University concluded that ethical leadership did indeed have direct effects on firms’ performance.

In other words, ethical leaders do not just affect employees’ behaviour or their feelings; their ethical behaviour directly boosts business performance, too.

Employee perception

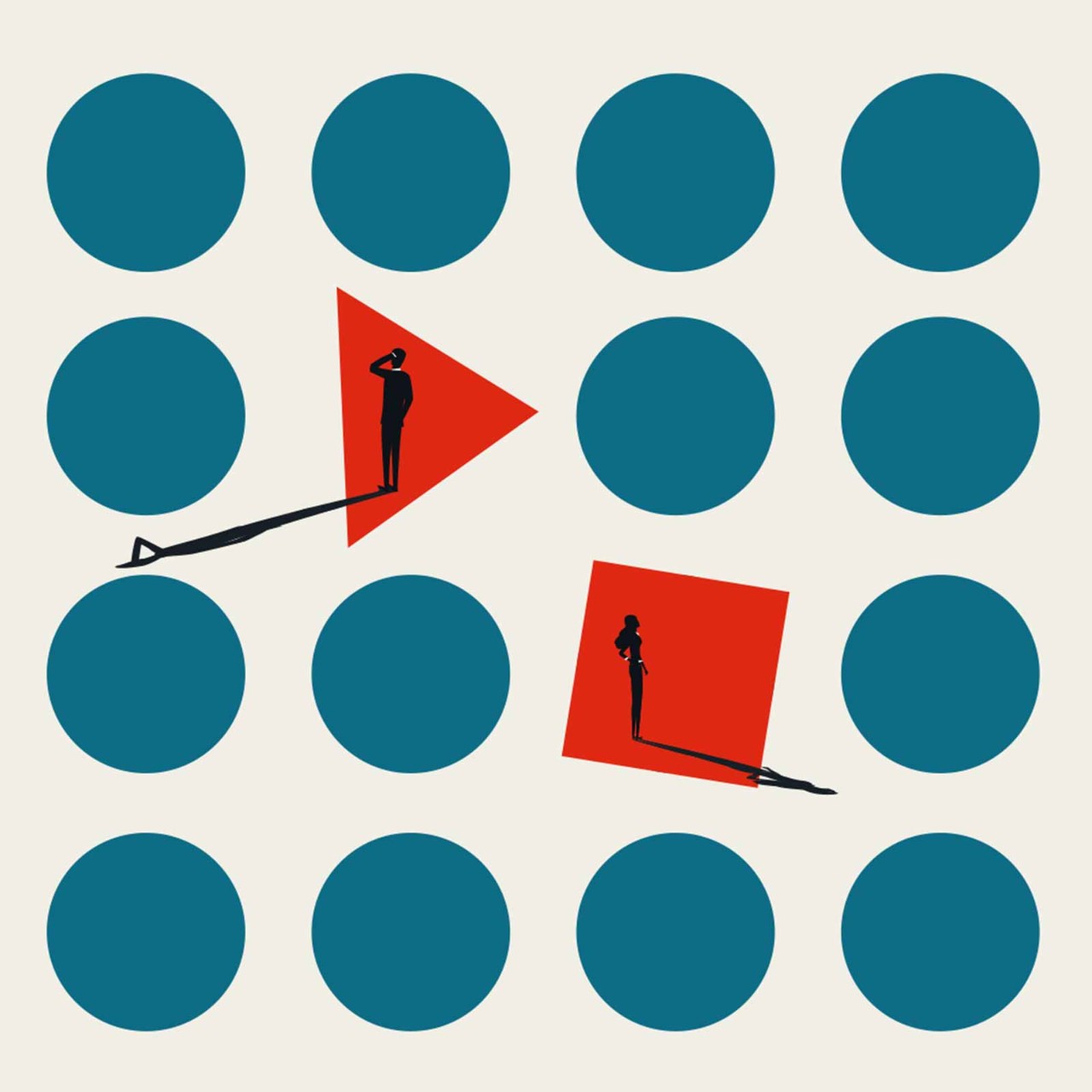

Crucially, ethical leadership is measured by the extent to which employees perceive a leader to be ethical. The benefits of ethical leadership only arise when everyone around a leader agrees that they are leading in an honest, trustworthy and honourable fashion.

So, if your aim is to lead more ethically, your first action should be to ask stakeholders around you how you are doing – ideally anonymously so that they feel able to speak freely.

In my experience of consulting in both the public and private sectors, many leaders have good intentions but inadvertently allow themselves and their teams to operate in ways that are not always as ethical as they could be.

Ethical behaviour by leaders directly boosts business performance, too

To help leaders understand more clearly the principles and practice of ethical leadership, I usually introduce them to a research-based framework that covers different components of behaviour.

One component concerns role clarification, which is measured by the extent to which stakeholders agree with questionnaire statements such as ‘This person explains what is expected of me and my colleagues’; ‘This person clarifies who is responsible for what’; and ‘This person indicates what the performance expectations of each group member are’.

Open to criticism

Leaders who do not communicate exactly who should be doing what – as well as what is not acceptable – could well leave themselves open to criticism that they are allowing unethical behaviour to go unchallenged.

Consider: have you ever communicated to stakeholders around you what they should not be doing as well as what they should be doing?

Another component of ethical leadership measures fairness, or the degree to which stakeholders disagree – not agree – with statements such as ‘This person holds me responsible for things that are not my fault’ and ‘This person pursues their own success at the expense of others’.

Again, leaders may unintentionally be perceived to be behaving unfairly if they do not explain clearly the reasoning behind their decisions. The implication: when making decisions that are likely to be unpopular, err on the side of communicating too much rather than too little.

A matter of integrity

A third component evaluates a leader’s integrity, or the extent to which stakeholders agree with statements such as ‘This person follows through on their commitments’ and ‘I trust this person to do the things they say’. Unfortunately, many people can bring to mind examples of leaders who say one thing but do another.

When making decisions that are likely to be unpopular, communicate too much rather than too little

To ensure stakeholders do not accuse you of hypocrisy and a lack of integrity, review the degree to which your actions match your rhetoric frequently. Did you perhaps make a promise in the past that you are now unable to keep? If so, explain how circumstances may have changed – and do so with humility and sincere apologies if necessary.

The extent to which leaders share power and decision-making also matters. This is typically measured by stakeholders’ agreement with statements such as ‘This person seeks advice from the wider team when setting organisational strategy’ and ‘This person is willing to reconsider decisions on the basis of recommendations by others’. Busy leaders often believe that they are best placed to make speedy decisions; however, ethical leaders take the time to not only solicit feedback but to use it as a check on their thinking.

There are other components of ethical leadership. But the key point is that such leadership is based on the perceptions of stakeholders, not on the beliefs of any given leader. Nearly all leaders believe themselves to be principled, decent individuals; unfortunately, surveys show that their employees and other stakeholders often think otherwise.

The situation is not irretrievable. In most instances, the disconnect arises because leaders fail to communicate their goals and expectations in sufficient detail – and to check that stakeholders not only understand but also agree with what has been said.

So, ask people around you how they see you. Listen and be humble enough to accept that you are not infallible; and demonstrate through your actions that you are willing to do what’s necessary to become the kind of role model that others want to work for and with.