At roughly the same time spring began in Canada, a deep winter freeze kicked in for crypto assets.

The price of a single bitcoin had already fallen from a year high of $68,789 in November 2021 to just over $47,000 in March 2022. Over the next three months, it plummeted to $17,600. There was a tiny recovery, but as June rolled into July, prices were falling again.

At the beginning of July, bitcoin was about 70% below its November peak. Ethereum, the second largest of the cryptos, was down about 80% to $1,014. The market capitalisation of crypto assets fell in six months to about a third of the $3 trillion it was worth at its peak. By comparison, stock markets are down about 20% from their highs.

At the time of writing, at least two lenders have stopped withdrawals, Babel Finance and Celsius. At least one crypto hedge fund, Third Arrow, did not meet a margin call. The exchange Hoo stopped all transactions. The selloff has been painful. Traders who bought on margin when the price was climbing were forced to put up more collateral or liquidate.

And the downward spiral continues. Inflation does not help. Fears of recession are pushing investors to pull their money. Regular people, driven by fear or need for cash, are pulling whatever money they can.

Putting faith in the tech is like trusting dusty, old-fashioned, two-column paper ledgers rather than the business itself

Taking the long view, however, the rise of bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies is nothing short of spectacular. Even at current beaten down prices, a single bitcoin is worth roughly six times more than at the end of 2018 and 40 times more than in 2015. Long-term investors are happy enough.

No protection

Hurt most have been retail investors that jumped into the crypto boom through the pandemic, putting savings and extra investment cash into an asset class that looked like it was skyrocketing and pushed into it by significant marketing campaigns – Crypto.com hired actor Matt Damon for an expensive Superbowl advert.

Unfortunately, individual investors often overlook the fact that these investments have no protection. Stocks represent ownership in a company, ideally a successful one. Bonds provide regular payments and cashflow. Cash in the bank (in Canada) is insured up to a certain level. Mutual funds provide protection through diversification.

None of this is true for crypto.

Crypto-trading platforms often provide decentralised financial (DeFi) products, essentially a parallel financial system that users can use to borrow, trade and even earn interest. This parallel financial system relies on stablecoins pegged to particular currencies, often the US dollar.

Through last year, the returns were quick, easy and hard to ignore, particularly when there was extra cash laying around from pandemic relief payments. Many of those stablecoins have collapsed.

The crash of cryptos is not a novel story. Cryptos crashed several times before, most notably in 2017 after China essentially blocked all cryptocurrency transactions.

This latest cycle highlighted the reality that cryptocurrencies are the most speculative of assets, backed mostly by the belief of supporters and their willingness to pour in money.

DeFi and the blockchain technology that underpins cryptocurrencies have a lot of uses, but putting faith in the tech is like trusting dusty, old-fashioned, two-column paper ledgers rather than the business itself.

Failures accelerate

Bitcoin itself and other cryptocurrencies have shown themselves to be quite ineffective stores of value. They don’t make for very good ‘money’ or provide any kind of reliability. And as their value drops, more people will lose money and more businesses will fail. Fitch Ratings expects that liquidations could accelerate if the price of bitcoin falls below $15,000. That is not far off.

The market gyrations have highlighted the need for more regulation and consumer protection. Canadian MP Michelle Rempel Garner introduced a private member’s bill in February to develop a framework and ‘talk about how to both protect people, and provide regulatory stability for growth in the crypto asset sector’.

There in a nutshell is the problem. It is tulip mania, again and again

This could prove difficult. A lot of crypto platforms are based outside Canada and not subject to Canadian laws. They are a lot like offshore online casinos. People and businesses invest in cryptocurrency at their own peril, and the peril is significant.

There is no obvious reason to think that cryptocurrencies won’t continue plummeting. Just as there is no obvious reason to think that the market won’t eventually bounce back. And there, in a nutshell, is the problem. It is tulip mania, again and again.

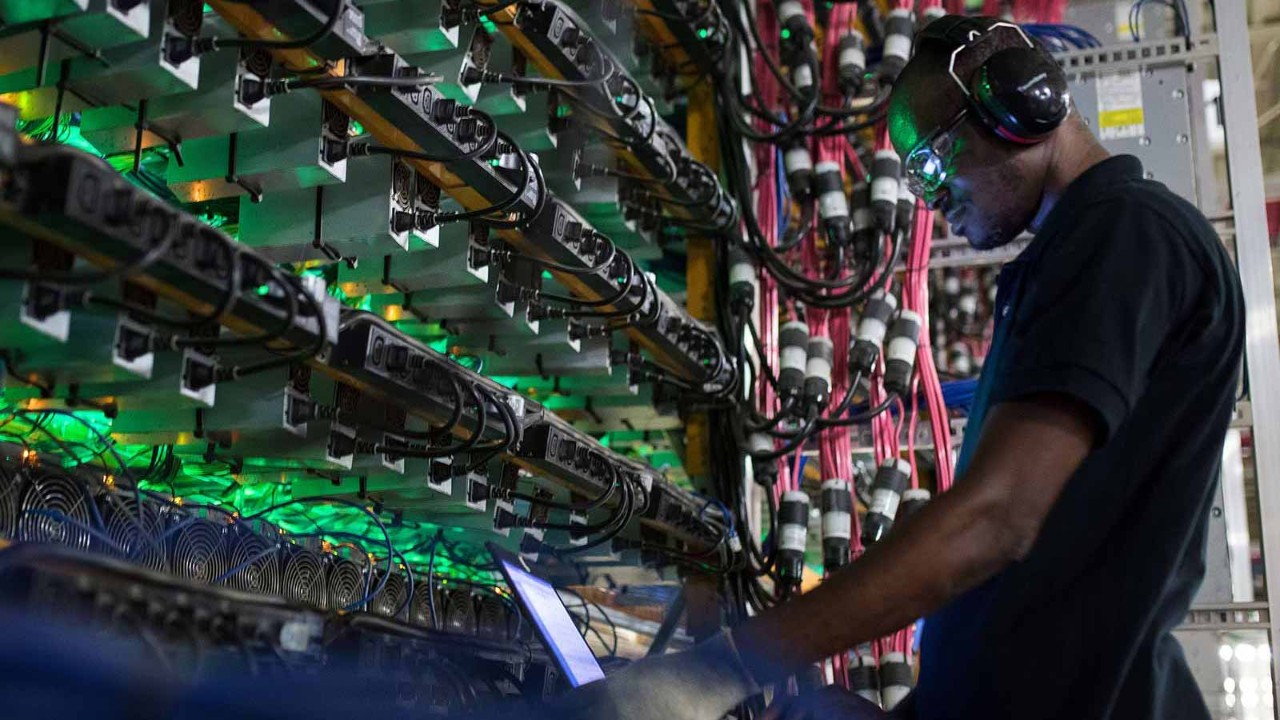

Nevertheless, crypto is now a trillion-dollar market that has the backing of governments and big companies. The province of Alberta, in Canada, for example, has put a lot of resources to attract cryptocurrency miners and exchanges. Further afield, the country of El Salvador has adopted bitcoin as legal tender and poured tens of millions of dollars of its fragile finances into the play.

All this infrastructure will not go away anytime soon. Bitcoin and other crypto assets are here to stay, especially those with the largest market capitalisations. Individual investors should be very, very careful (even wary) about how much money they put into them.

The crash has accentuated, highlighted and underlined the dangers of cryptocurrencies. It would be foolish to ignore all these warnings.