The government’s much-heralded Tax Day, which promised to provide details on the Treasury’s current thinking, proved to be more of a damp squib, according to many commentators, including Jason Piper, ACCA’s head of tax and law.

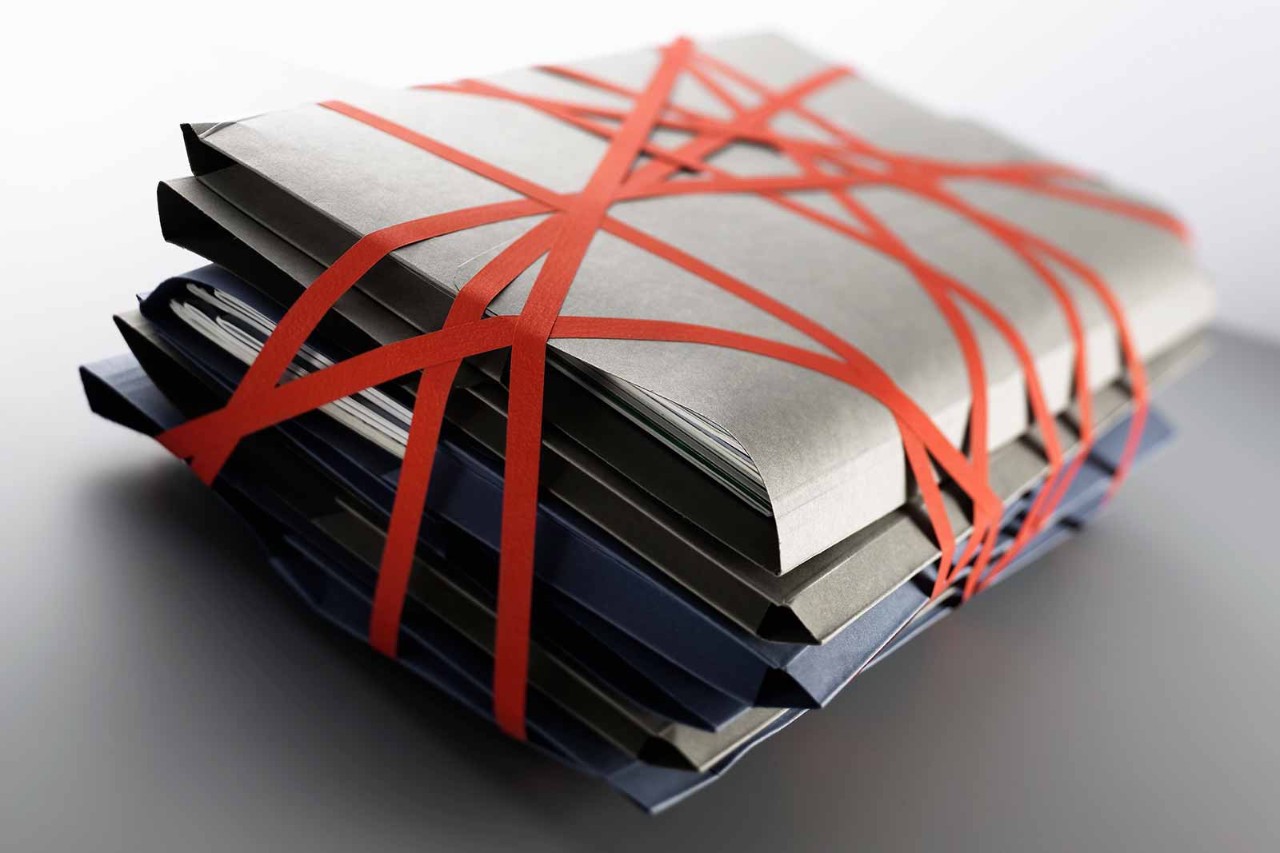

But amid the 30-odd consultations and responses to consultations published on 23 March was one subject that has managed to generate considerable debate. Under the heading ‘Making Tax Digital’ (MTD), the government confirmed that it would introduce legislation later this year to extend MTD to income tax self-assessment from April 2023.

This move would follow the introduction of legislation that extended MTD for VAT to smaller VAT-registered businesses from April 2022. The Treasury sees MTD as the backbone of a ‘modern, digital tax service’, where taxpayers not only report their taxable income in real time but also pay it on a more regular basis.

But to whom would this extension apply? Employees pay income tax through the PAYE system, literally paying their taxes at the same time as earning their income. There would then be a levelling up, or down, of total tax liability for a tax year through the self-assessment process that takes into account areas such as additional income, benefits in kind and capital gains.

The self-employed, however, only pay tax on their earnings once every six months under the payment-on-account system, with their total liability calculated through the annual self-assessment process. This, in effect, means that there is a 10-month gap between the end of the personal financial year (5 April) and the deadline for filing a self-assessment form and paying any outstanding tax (31 January). This calculation is then used to predict future income for payment on account.

By switching to an MTD method of declaring income as and when it is earned, the Treasury is hoping to be able to get its share of that income on a regular, timelier basis.

The government’s euphemistic use of the word ‘timelier’ should be translated as ‘earlier’

Managing fluctuations

But a number of interest groups argue this is far from simple. Income can be seasonal (think tourism and events – even turkey farming) and, likewise, costs may only be incurred on an annual basis, or at least less frequently than on a monthly basis.

As Andy Chamberlain, director of policy at IPSE, the self-employed lobby group, says, there are a number of unanswered questions.

‘First, many self-employed people’s incomes fluctuate substantially throughout the year, and while the current annual system accounts for these and ensures self-employed people pay the right rate, it is not clear how this would work with rolling in-year taxes. It is also not yet clear how this would work with late payments, which are a substantial problem for the self-employed.’

Administrative burden

Chamberlain adds that he would want to be satisfied that this proposal would not pile even more of an administrative burden on the self-employed, many of whom have quit running their own business during the pandemic in any case.

‘There seems a risk here that rolling administrative tax responsibilities could be added to the requirement to complete some form of annual tax return, which would eat even further into freelancers’ vital working time,’ he says.

David Barton, a tax partner at RSM, notes that there are 45 questions raised in the government’s call for evidence, a large proportion of which consider how the adverse effects of earlier and more regular tax payments can be mitigated. These comprise chiefly the need for businesses to estimate the tax due before a final tax return has been, or can be, prepared, and effectively manage working capital without negatively impacting business investment.

‘What does not appear to be in doubt is that the intention is to bring payment dates forward, with the government stressing that this will make tax compliance easier for many businesses,’ Barton says. ‘A desire to improve cashflow to the Exchequer would not, on the face of it, appear to have contributed to the government’s thinking.’

Question of timing

Indeed, Piper argues that such a move could actually have a damaging impact on government cashflow and its ability to budget. ‘The time delay between assessing how much a taxpayer owes and the date at which point that money is due allows the government to plan accordingly. Any economic shock, as seen during the two lockdowns, can therefore be anticipated,’ he says.

‘However, if payments are to be made in real time, then any slowdown will be reflected in an immediate real-time fall in tax receipts.’

Piper points out that there is also another consideration that should be borne in mind. If the government does introduce a system of real-time payment, then at some point taxpayers will be required to pay not only what they owe under the current self-assessment regime but also what they owe under any new real-time payment scheme – a double whammy of tax payments.

The alternative would be that the government foregoes payments on account during the transition period. But if history is anything to go by, this would seem to be unlikely.

As Barton points out, the government’s euphemistic use of the word ‘timelier’ should be translated as ‘earlier’.