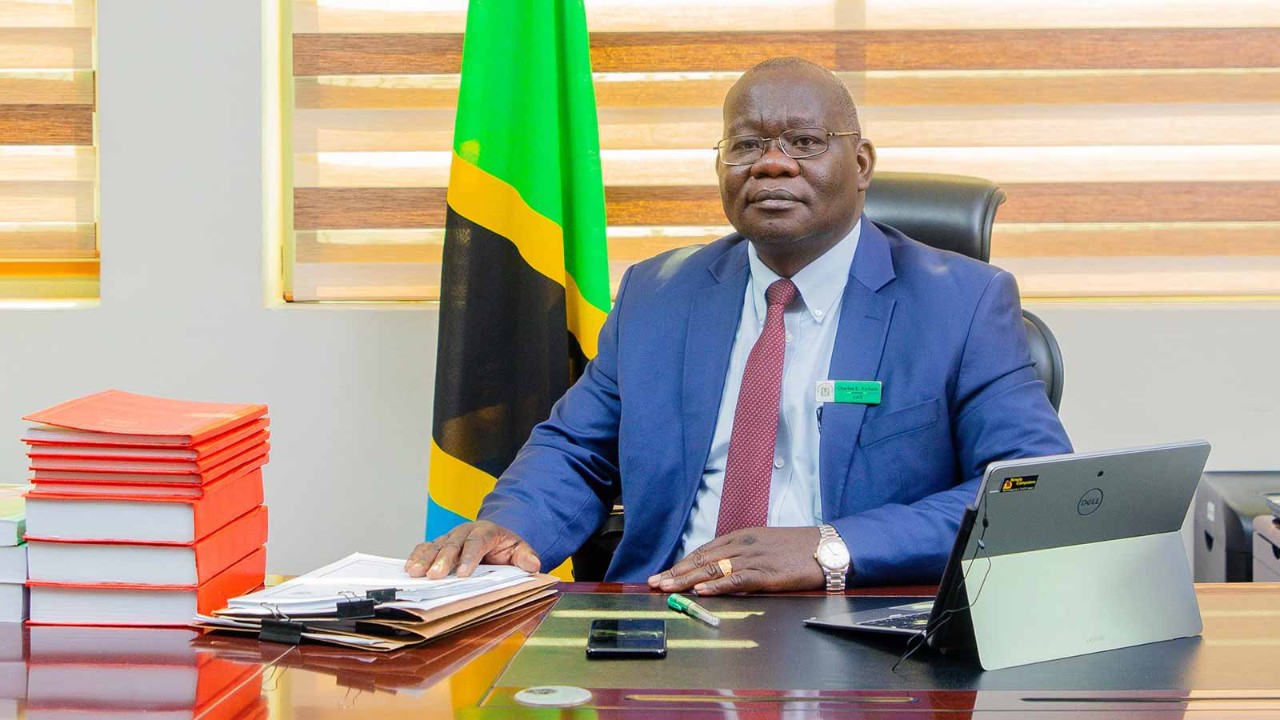

If anyone was unsure what the role of Tanzania’s controller and auditor general (CAG) involved, they were left in no doubt earlier this year.

Within days of taking office in March, the country’s president, Samia Suluhu Hassan, was presented with a damning report from CAG Charles Kichere. In it, Kichere revealed endemic levels of financial mismanagement in state agencies. As a result, Hassan immediately suspended the head of the Tanzania Ports Authority, as well as calling for the CAG to hire additional auditors to work more closely with the country’s Prevention and Combating of Corruption Bureau.

A further report, released in July, uncovered irregularities in development payments from the central bank to Tanzania National Roads Agency (Tanroads) and Tanzania Ports Authority, among others.

‘I do my work without fear or favour, without any interference whatsoever from the arms of the government’

CV

2019

Controller and auditor general and head, National Audit Office of Tanzania

2019

Regional administrative secretary, Njombe region

2016

Deputy commissioner general, then commissioner general, Tanzania Revenue Authority

2012

Chief accountant, Tanzania National Roads Agency

2000

Internal auditor, Tanzania National Roads Agency

1997

Internal auditor, Unilever Tea Tanzania and Unilever Tea Kenya

Diverse expertise

Kichere, who is also head of the National Audit Office of Tanzania (NAOT), has a wide remit, reviewing the practices, policies, frameworks and internal controls governing public finance management in the country.

Helping him is a highly qualified multidisciplinary team that, as well as certified public accountants, includes a wide range of disciplines from engineers, lawyers and IT specialists to procurement experts, environmental specialists and economists.

‘This diversity of expertise and experience adds credibility to my office and our work,’ Kichere says. ‘We need it in order to cover the whole of government business and operations.’

New recruits from non-audit backgrounds undergo a year’s rigorous training to develop auditing skills before starting assignments, and they are also encouraged to undergo accountancy training. At the same time, accountants are encouraged to expand their professional knowledge, thus maximising their impact in an environment of limited resources.

In this, Kichere practises what he preaches – he has a law degree, and a degree in accounting from the University of Dar es Salaam. ‘Having both sets of skills helps me analyse complex situations or problems and advise the best solutions based on strong reasoning and critical thinking,’ says Kichere, whose previous roles have included internal auditor at Unilever, chief accountant of Tanzania National Roads Agency and commissioner general of the Tanzania Revenue Authority.

Tech is the key

Under its current five-year plan, which runs until 2025/26, digital transformation is the NAOT’s key goal. ‘As auditors, we need to be ahead in terms of technology utilisation,’ Kichere says. This includes the deployment of upgraded audit documentation software, currently being piloted. ‘This is centralised, which makes it possible for real-time review of work carried out by our teams in the field,’ he explains.

Technology has proved useful in tackling the challenges of gaining sufficient audit evidence during the Covid-19 pandemic. While Tanzania escaped a full national lockdown, the NAOT’s auditors were sometimes unable to travel to the country’s embassies and missions abroad to check their accounts.

‘We needed to be able to provide assurance to the public that the resources in our offices abroad were efficiently, economically and effectively utilised,’ Kichere says. ‘If you have limited access to people and to information, this can be a loophole for culprits to engage in corruption. But we are employing techniques like pulling data to our offices so that we can analyse the data here, instead of relying on going to the client in order to obtain evidence.’

The NAOT is also keen to explore new ways to improve performance through technology and has established an innovation lab, staffed, Kichere says, by tech-savvy millennials, headhunted from the country’s universities. ‘We station them in a place where they can relax, work independently and come up with new ideas,’ he says.

Kichere also wants to improve the working environment for his staff in regional offices. ‘We need to modernise our offices – not only the buildings, but also the tools for our auditors. Every auditor should have a state-of-the-art laptop.’ While all staff currently have laptops, some are outdated and need replacing.

‘We station our innovation lab staff in a place where they can relax, work independently and come up with new ideas’

National Audit Office of Tanzania

The mission of the National Audit Office of Tanzania (NAOT) is to provide high-quality audit services through a modernisation of functions that enhances accountability and transparency in the management of public resources.

It is required to report at least once a year on all three arms of the government: the executive, legislature and judiciary. This includes assessing the effectiveness of budgeting processes, accounting and reporting, fiscal planning, expenditure policies, control over budget execution or administration, internal control systems and management of funds from stakeholders including development partners.

The office produces around 900 reports a year, resulting from a variety of audit types, including financial, performance, compliance, forensic, information systems and environmental audits, as well as technical or special audits addressing targeted issues. It also issues annual general reports compiling key issues noted during the NAOT’s audits for a financial year, alongside recommendations for improvements.

The 950-strong workforce include more than 800 auditors, based in Dodoma and in regional offices.

Improving communication

Another key goal is to improve communication with citizens, in order to enhance transparency and accountability in the management of public resources. A welcome addition has been the ‘citizen report’, written in more simple language.

Improving communication with the legislature is also a priority, with a particular focus on the core oversight committees for public accounts, local authorities and budget.

‘Parliament is responsible for reviewing our report recommendations and sometimes issuing directives to the government on how to deal with our audit recommendations,’ Kichere says, ‘so having a good relationship is key for my office.’

Access all areas

Kichere has no doubt that his office has the sufficient legal and constitutional teeth to operate effectively. ‘I have unlimited access to any information, to any person in the country,’ Kichere says. ‘I have the mandate of planning my audit: what to do, where to audit, what type of audit to conduct. So I do my work without fear or favour, without any interference whatsoever from the arms of the government.’ This is, he adds, strengthened by the protected nature of the CAG’s position.

The CAG in Tanzania is appointed for a term of five years, which can then be renewed. ‘I want to ensure that after my tenure, this office has changed to be a modern office, using tools for data analytics, with qualified, multidisciplinary staff and a teamwork spirit,’ Kichere says.

He is clear about what he would like to achieve in his first five years: ‘I want to ensure that every single cent of the taxpayer’s money is reviewed and audited; to provide assurance to the general public of the United Republic of Tanzania that their finances, their taxes, are properly utilised and revenues are properly collected and used by the government.’