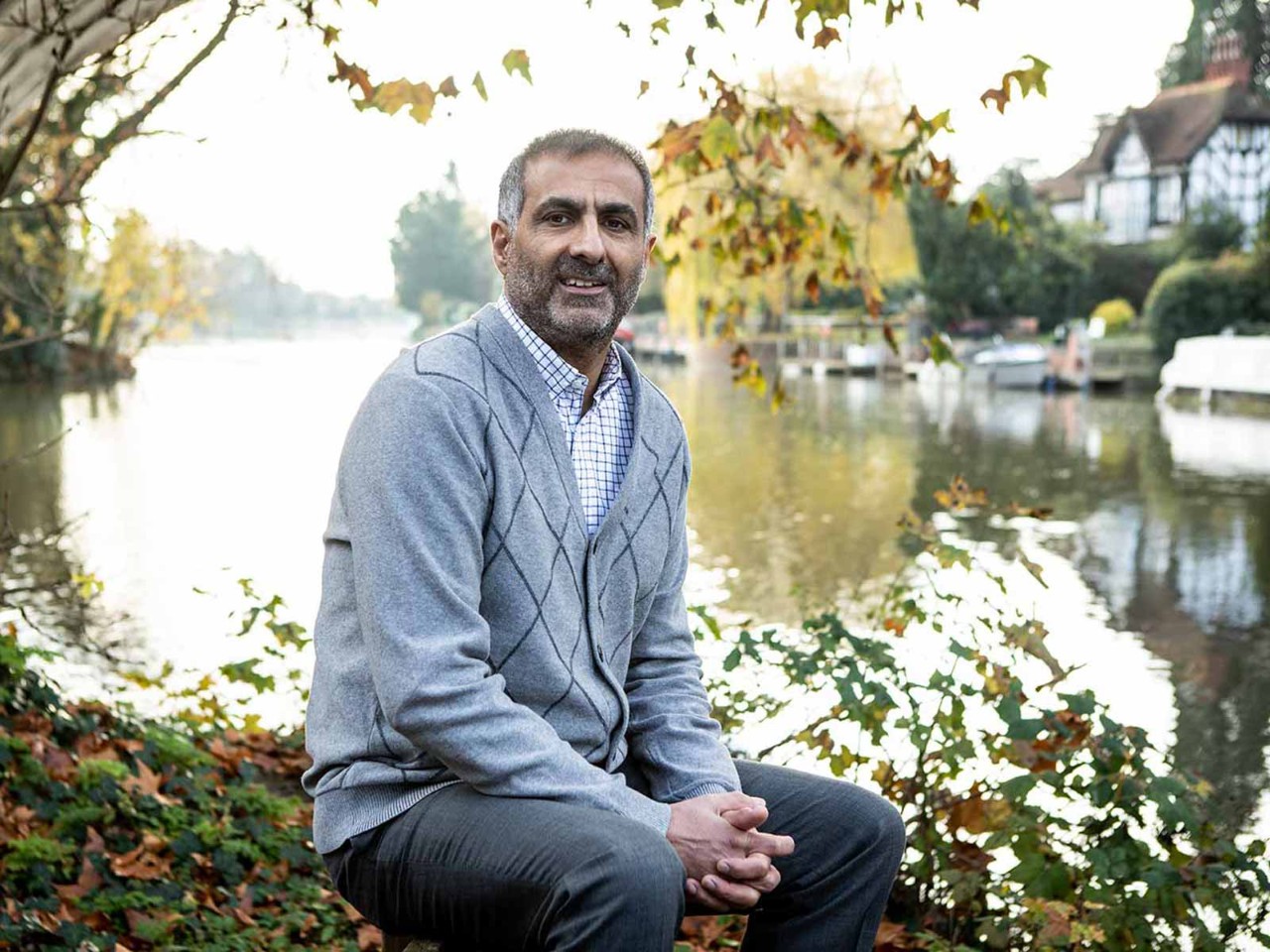

A growing number of companies are publishing roadmaps to net zero by 2050. Some of these maps have been signed off by third parties, lending a reassuring veneer of credibility. I have always enjoyed reading the small print, so I decided to look at some of these plans in more detail.

It turns out that many of these aspirations, particularly for carbon-intensive industries, are built on the shakiest of foundations.

There is an abundance of hype and a lack of major private investment

This may sound arcane but I think it increasingly matters to accountants. There is growing pressure on auditors to include climate risks in financial statements. It is a statement of the obvious that the biggest emitters face potentially the biggest direct risks. Legislators and campaigners are focusing their fire on the sectors that cause the most damage.

The irreplaceables

I have been looking at three industries: cement, steel and road freight. These three sectors produce about 20% of global greenhouse gas emissions. They are also deeply embedded in day-to-day living. It is impossible to imagine a world without access to steel, concrete and delivery trucks.

Arguably the most effective way of decarbonising electricity production is by building more wind turbines. Unfortunately, wind turbines require a lot of steel and concrete, which no-one ever wants to talk about. You can’t expand wind turbine capacity and cut steel and cement production at the same time.

A similar argument can be made about road freight. Covid brought the convenience of home deliveries to many more people, and it is hard to see this trend reversing. Road freight is not a sunset industry.

These three sectors are not just here to stay; their importance may actually increase over the next 10 to 15 years. If we can’t reduce demand, the only other option is to decarbonise supply.

There is no large-scale investment in carbon capture because the business case doesn’t stack up

Where’s the money?

This is where it all starts to fall apart. The roadmaps depend on technologies that don’t exist today in commercially viable forms. It’s a point that tends to be obscured, even in the small print.

When I started out as an industrial analyst, fuel cells were considered to be about five years away. The theory was that fuel cells would replace internal combustion engines for cars and trucks. Almost 30 years later, they are still at least five years away. There are many explanations for this, most of which boil down to hype, blustering and credulousness. There was one very big warning sign back then, though: no company was investing large sums in production capacity.

I think we have the same situation today with carbon capture and storage (CCS), which is supposed to trap and cache the carbon dioxide emitted by steel and cement plants. There is an abundance of hype and a lack of major private investment. My strong suspicion is that CCS is a rerun of the fuel cell saga. There is no large-scale investment in CCS because the business case simply doesn’t stack up.

Unfortunately, there are few other options to decarbonise cement, steel and road freight. Hydrogen or biofuel may become viable for heavy trucks, but the manufacture of steel and cement inevitably involves releasing CO2. There are no easy answers here and certainly not in the next 10 years.

I suspect the auditors are also unaware of the central fallacy

Roadmaps of fancy

All of which leads me to question the purpose of these net-zero roadmaps. Are they meant to inform or deceive? The casual reader has no way of knowing that the roadmap is more akin to science fiction than documentary. I suspect that the auditors are also unaware of this central fallacy.

I believe that fighting climate change is crucial for future generations. To effect change, we must base our decisions on rational, scientific analysis. Pretending to have the answer when you don’t is not just dubious, it creates an inappropriate sense of complacency.

More information

For more insights, courses, CPD and webinars on sustainability, visit ACCA’s sustainability resources