Returning to the office after a long time spent working from home during the Covid-19 crisis will come with mixed emotions for many.

But what is clear is that the very notion of office working has been significantly disrupted.

‘We’ve all been through something together, a once in a lifetime event, and traumatic episodes always bring people together,’ says Shola Kaye, communication specialist and speaker on empathy and inclusion in the workplace. ‘Shared experience means people share more common bonds.’

Those bonds have been strengthened through not being able to ‘unsee’ what’s been seen in video calls, as elements of colleagues’ home lives invade the digital work environment.

For better or worse, this shared experience has forced individuals’ two lives – the work one and the private one – into a single being.

This could therefore be a moment not only for employees to reframe themselves in the context of their working environment, but also for leaders to redefine their leadership, to become more empathetic, to actually allow people to bring their whole selves to work, and for organisations to then fully benefit from their employees.

Unlock potential

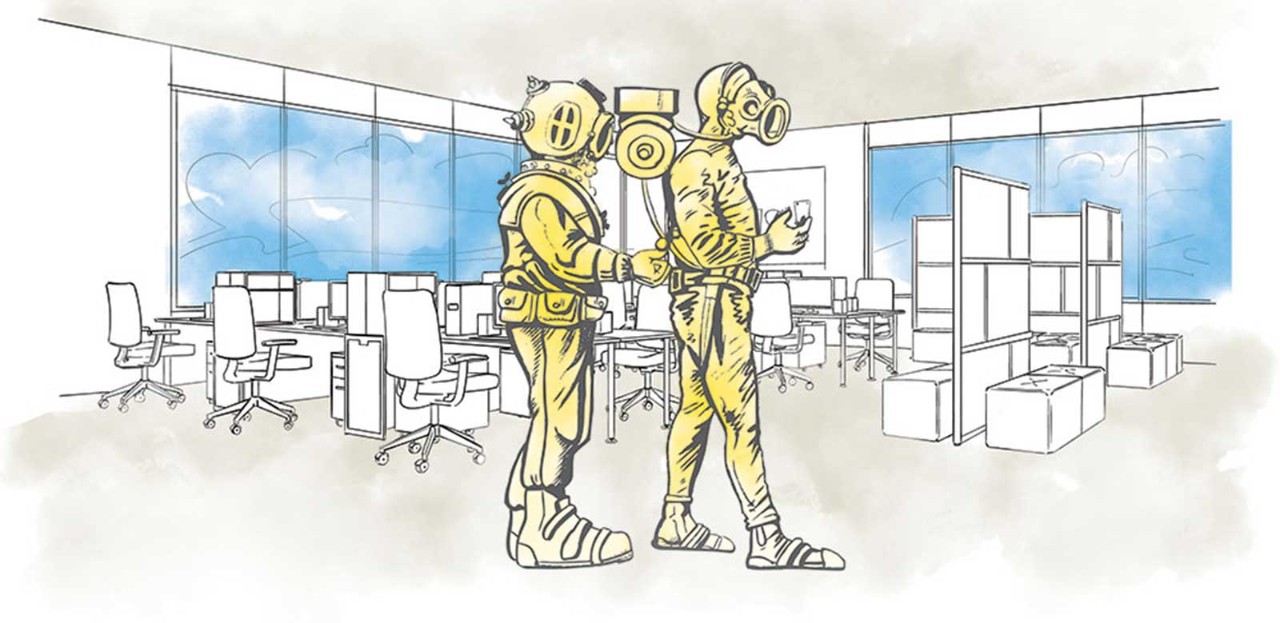

Kaye uses two analogies to describe the hidden potential of people who feel discouraged from bringing all of themselves to work:

- the iceberg, with only 10% showing above the surface, while the hidden 90% might contain exactly the skills and abilities someone was hired for in the first place

- the deep sea diving suit, where someone feels packaged up, stifled and unable to be themselves, and forced to move more slowly

The notion of work being a stifling place has been challenged over the past few decades by younger generations, the businesses they’ve set up and their influence on established organisational culture.

But beware false progress. Heather Smith FCCA, a 100% digital practice owner and nomad, points out that the corporate world likes to harmonise around innovation, while its workforce, by and large, still follows a paint-by-numbers sense of fitting in, even in some seemingly hipster modern accounting practices.

‘The leading accountant has a beard and tattoos, and every member of the team is dressed similarly. Their brand is rebellious, but they are cookie-cutter images of each other,’ Smith says.

Perhaps harder to challenge and dispel are the unwritten codes, as well as our biases, unconscious or otherwise, that keep the largest part of the iceberg beneath the surface.

Empathy, finally?

So is this a moment to truly address these biases, to provide millennials with the empathetic workplace that they may crave?

‘I feel there will be a boost, but adoption within an organisation will depend on the leadership,’ says Andy Salkeld, author of the book Life is a Four-Letter Word: A Mental Health Survival Guide for Professionals. ‘If the leadership of an organisation wants people in an office, in suits and in a stale environment, no matter how many millennials want an empathetic environment, it won’t change.

‘Culture change requires a change in leadership. It’ll take time, but it’ll happen.’

People also require tools to be empathetic, to understand their own biases and the effects they have on others.

‘Empathy is not much good without proactive and protective action,’ says Jo Yarker, a director at Affinity Health at Work and senior lecturer at the University of London. ‘Business In The Community’s Mental Health at Work 2020 report shows that employees feel that employers are more supportive of their mental health since the outbreak of the pandemic. Many organisations have been proactive in building awareness and offering a suite of tools, such as Headspace, to support mental health.

‘But they also need to look at how jobs are designed and at working conditions. Do staff have manageable workloads? Do they have autonomy over how they do their work? Do they have access to practical and emotional support from colleagues and managers?

‘Without good working conditions, empathy becomes redundant.’

Look before you leap

So what can organisations and individuals do?

‘Ask teams what changes they’d like to bring to the workplace and see what can be accommodated,’ Smith suggests. ‘Don’t make a knee-jerk call without consulting your staff.’

While the deformalising of work during lockdown will be preferred by some, others may feel uncomfortable with the less formal approach and miss the clear boundaries that the protocols in a physical workspace encourage.

Introverts may be particularly wary of a return to the office, especially one in which bringing ‘more’ personality is encouraged. ‘Introverts, in many companies, are already less productive than they could be due to the company culture and communication styles. Extra personality “requirements” spilling into the workplace could be detrimental,’ says Jon Baker, professional speaker and coach at Introvert in Business.

Pick the best bits

As we start to transition back to the workplace, it is a great time to think about what has worked well, what changes have been welcome, and what they would like to keep hold of, says Yarker.

‘The hard-fought battle for flexible working has been turned on its head, and organisations recognise that lots of work can be done away from the office. So in the future we may find that we are doing lots of our work at home, but coming to the workplace to build relationships and social connections. In doing so, it is likely we will bring more of ourselves to the office environment.’

In the end, people will naturally bring more of their life with them back to the office, given it’s now part of the unseeable.

‘The best thing anyone can do to bring their personality into the office is to actually bring their personality into the office,’ Salkeld says. ‘Don’t shy away from being yourself.’